029. Lola Flash

A Visionary Lens on Queer Life, Resistance, and Radical Possibility

Introduction

Lola Flash (they/her) is a 66 year old photographer, former educator, and lifelong activist whose work spans over four decades. Born in 1959 in Montclair, New Jersey, they have devoted their career to portraiture that challenges and dismantles stereotypes around race, gender, sexuality, age, and identity. Her images are rooted in community advocacy and emerged in the 1980s during the AIDS crisis in New York City, using photography not just as documentation, but as a tool of resistance and remembrance. Over the years, their photographs have found their way into major public collections including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Whitney Museum of American Art, Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the Brooklyn Museum, marking her as a significant figure in contemporary photography and visual activism.

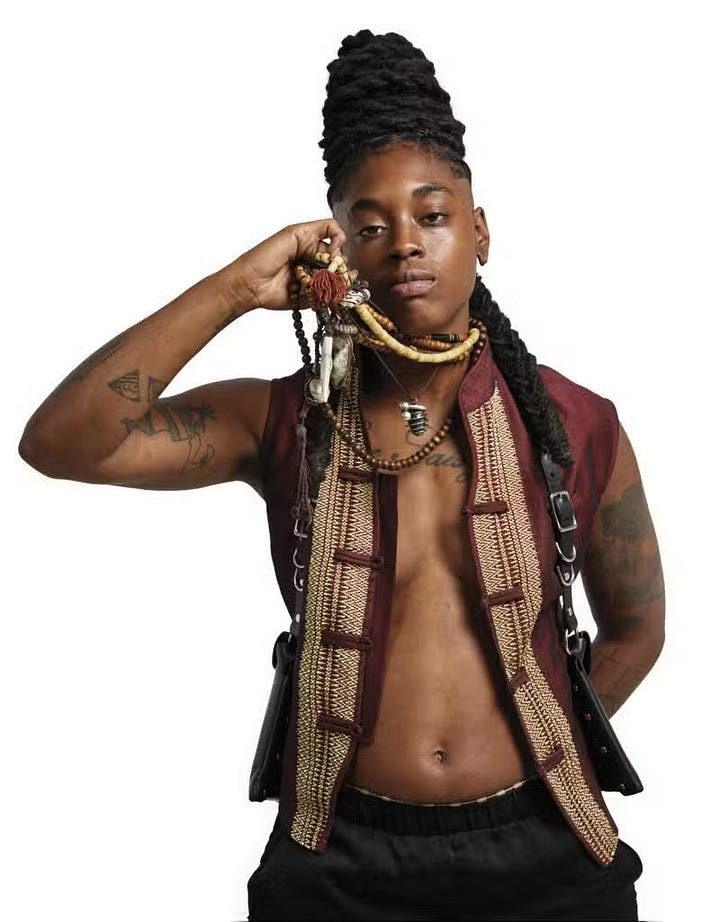

But Lola’s legacy is not only institutional. Her work insists on dignity and presence for communities persistently marginalized. Using portraits, they center those whom society often renders invisible: queer elders, Black bodies, women over seventy still living with purpose, gender-nonconforming and gender-fluid individuals, and more. Her photographs are deeply personal but reach far beyond the individual, they function as archives of memory, identity, resilience, and communal survival.

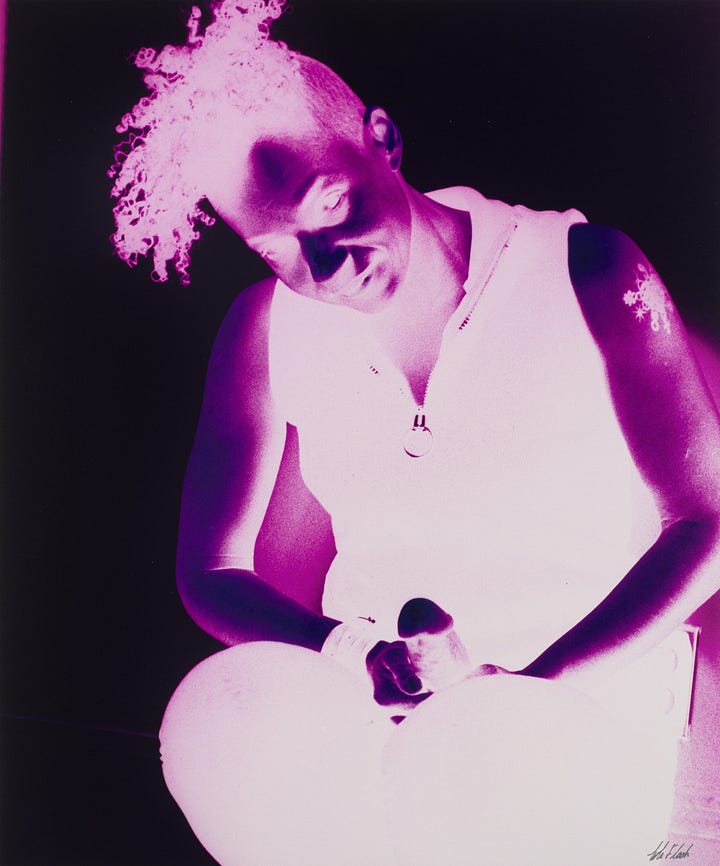

Throughout their career, Flash has maintained a commitment to both formal experimentation and social justice, weaving together aesthetics and activism. Whether working with slide film color inversion, large-format 4×5 cameras, or contemporary digital tools, she adjusts her medium to the gravity and needs of their subjects. Her journey from darkrooms to museums underscores an ongoing refusal of invisibility and a determination to assert visibility, voice, and legacy for the communities they photograph.

Early Life and Background

Cultural and Personal Influences

Lola grew up in Montclair, New Jersey, in a family deeply rooted in education and civic engagement. Their parents were both public-school teachers, and on her mother’s side, they are the fourth generation residents of Montclair. Their maternal great-grandfather, Charles H. Bullock, played a significant role in establishing Black YMCAs in Montclair, Brooklyn, Virginia, and Kentucky; and her paternal great-grandmother is the namesake from whom “Lola” originates. This lineage of educators, community builders, and generations invested in Black civic life laid a foundation for Flash’s understanding of culture, history, and responsibility.

From that upbringing emerged a sense that art can and should serve community. Flash’s family legacy wasn’t about art for art’s sake, but about creating conditions for learning, uplift, and collective resilience. That orientation likely predisposed her to view photography not just as a hobby or profession, but as a vehicle for social justice, memory, and representation. In their work, the threads of ancestry, communal obligation, and survival consciousness are often visible through the bodies they photograph and the narratives they choose to center.

As they matured and navigated their own identity as a Black, queer, gender-fluid woman, those early influences combined with lived experiences to shape a worldview in which visibility and representation are essential. The intersection of race, gender, sexual orientation, age, and history becomes a central lens through which Flash views her subjects and frames her work.

Early Exposure to Art and Education

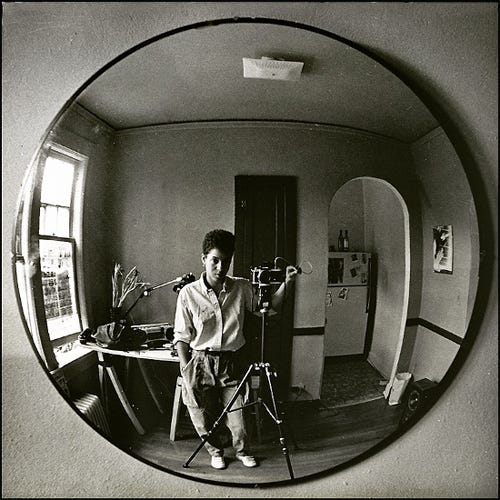

Flash’s earliest experiences with photography began in childhood: first with a small Minox camera, then later with a 35 mm when her mother supported their passion by helping them set up a darkroom. In high school, she took portraits for the yearbook, early evidence that they were not only interested in photography technically, but socially: documenting peers, capturing identity, and representation. That domestic darkroom practice, inherited from family support, seeded a conviction that photography could be more than light and lens, it could be a path to visibility and memory.

“My mom’s boyfriend gave me a Minox- it was like a toy. That was the beginning of my framing the world. In high school I got a 35 mm and I took photos of my friends. My mother bought me a dark room and this made me realize photography was going to be my life. First, I wanted to be a scientific photographer and shoot through a microscope. But when I got to college, I decided I wanted to be a fine arts photographer and make images about identity.”

— Lola Flash in an interview with Kate Walter for Senior Planet

Flash went on to attend the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), graduating with a B.A. in 1981, under the mentorship of artist and art historian Leslie King‑Hammond. During their time there, she began experimenting with slide film and a distinctive technique: developing slide film on negative paper, inverting color relationships. This “cross-colour” method would become one of their signature visual strategies. That experimentation represents more than aesthetic choice: it is an early act of critique, challenging conventions of representation and the standardized rendering of skin tone, identity, and visibility.

Later, Lola earned an M.A. with Distinction from the London College of Printing. Time spent abroad exposed her to different cultural and publishing contexts, including alternative and queer media in London, broadening their understanding of audience, distribution, and how photography might exist beyond gallery spaces. This global exposure balanced against her New Jersey upbringing and New York activist milieu, resulting in a hybrid sensibility: formally rigorous, socially grounded, and globally aware.

Artistic Influences and Style

Key Influences

Flash’s artistic style and thematic concerns draw from multiple, overlapping influences: family legacy, activist politics, queer editorial culture, and the history of Black portraiture. Growing up in a lineage of educators and civic leaders endowed them with a sense that cultural production can serve community rather than only individual ambition. That heritage highlights their respect for elders, elders’ stories, and collective memory, motifs that recur throughout her later work.

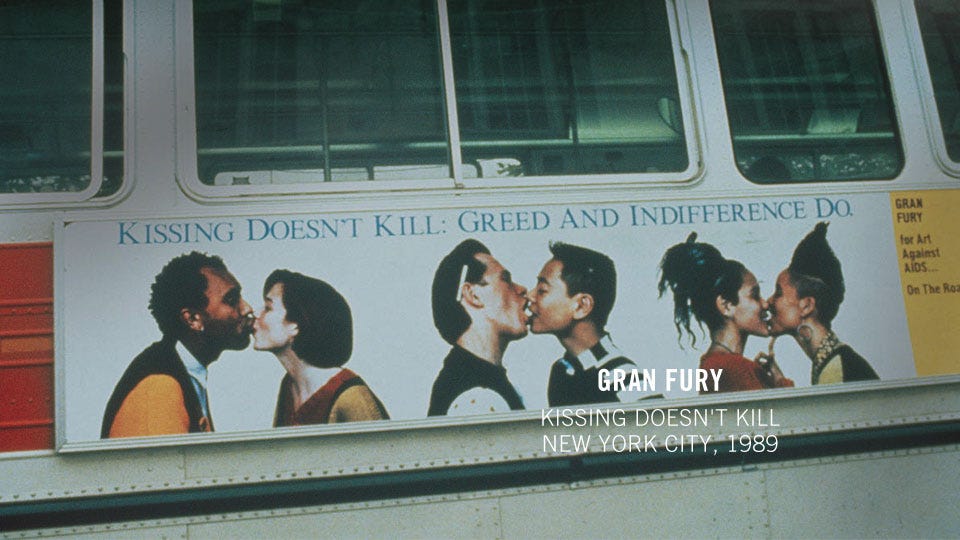

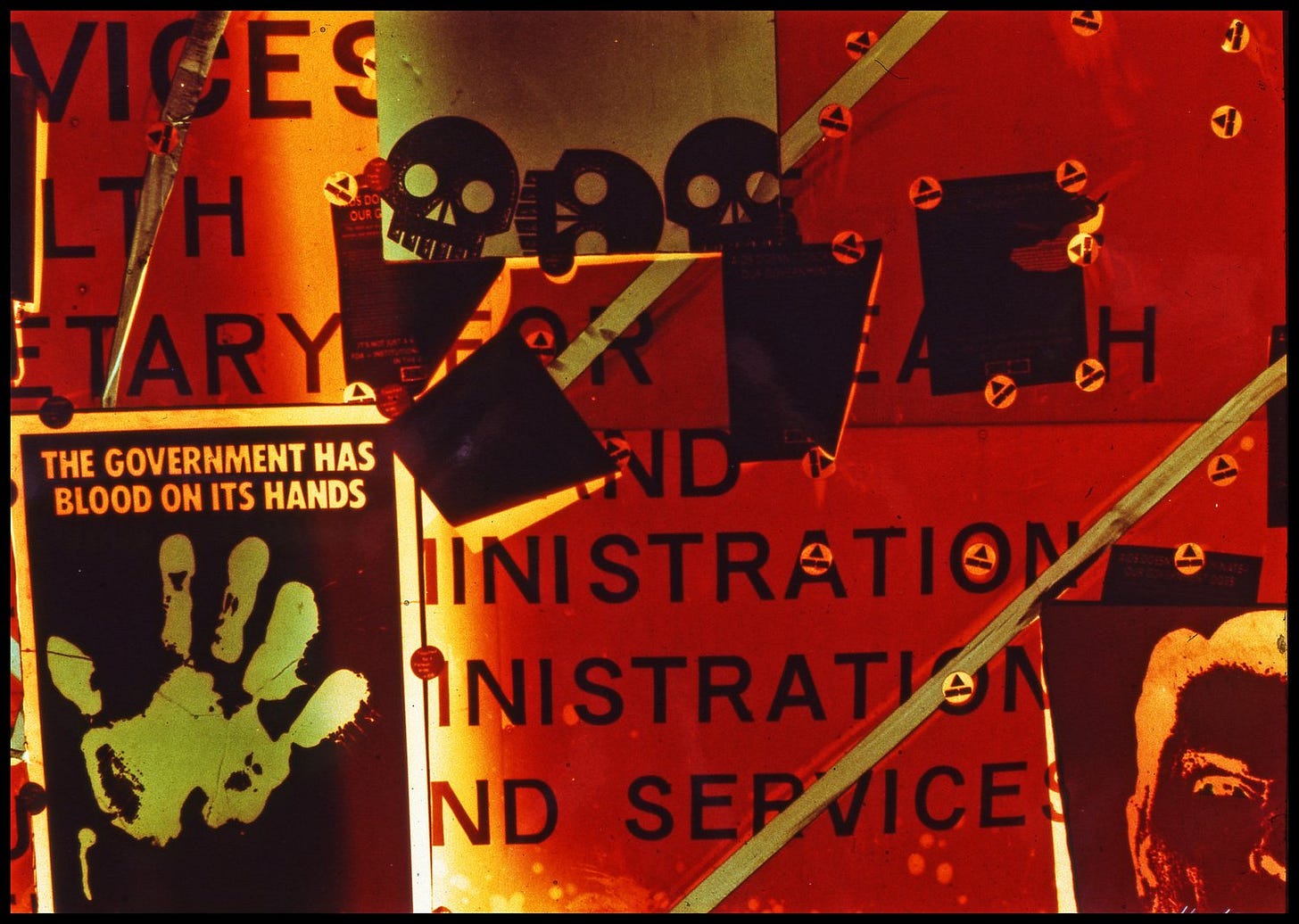

At the same time, the tumultuous social and political environment of New York in the 1980s, especially the AIDS crisis, deeply shaped Lola’s priorities. As an active member of ACT UP, and collaborator with the artist-activist collective Gran Fury, Flash learned first-hand how images could operate as tools of protest, remembrance, and visibility. The 1989 “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do” poster, featuring Flash and their then-partner, remains an iconic testament to how art and activism could merge to challenge complacency and prejudice in public spaces.

Their years in London, working for alternative lifestyle and queer publications as well as teaching, exposed her to editorial photography and international visual cultures. That broadened exposure contributed to their ability to navigate between intimate, community-rooted portraiture and more public, globally distributed photographic work. This balance between grassroots and institutional, between intimacy and publicness, is a through-line across their career.

Finally, the formal experiments in color, tone, and medium, especially her cross-colour technique reveal a strong influence of technical curiosity and conceptual critique. By inverting colors, warping familiar visual cues, and later shifting to large-format cameras or digital tools, Lola makes visible the social and psychological codes embedded in photographic conventions. In doing so, they push viewers to question what “normal,” “beauty,” and “identity” even mean in photographic representation.

Art + Identity

For Flash, identity is never incidental, it is integral. Much of their work centers Blackness, queerness, gender fluidity, age, and the ways these intersect. Through portraiture, they foreground individuals often marginalized by mainstream visual culture: elders, queer and gender-nonconforming people, women over seventy, people of color, trans and gender-fluid individuals. In doing so, she refuses invisibility and asserts complexity, dignity, and presence.

Her cross-colour technique is particularly meaningful in this regard. By inverting or distorting conventional color relationships, such as transforming blues into reds, whites into blacks, or altering skin tones, they unsettle conventional photographic “truths.” This distortion becomes a political gesture: a challenge to the visual norms that historically marginalize darker skin tones or queerness, and a disruption to the default gaze through which identity is often filtered.

But Lola does not only deconstruct. They also affirm. Portraits from series like SALT celebrate women over seventy who remain active, vibrant, and purposeful: reclaiming age and experience as powerful, defying cultural erasure and ageism. Her portraits of LGBTQIA2S+ elders and community members in series like LEGENDS memorialize lives and histories that mainstream culture too often overlooks. In these works, identity becomes a source of pride, inheritance, and collective memory.

Art + Activism

From the very beginning, Flash’s art and activism have been inseparable. In the late 1980s, as the AIDS epidemic ravaged queer communities in New York, Lola joined ACT UP and contributed to the “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” campaign, not simply as a photographer, but as a visible queer presence on the poster itself, refusing shame, fear, and silence. The choice to put herself in front of the camera, not just behind it, signaled a deep personal commitment to activism, visibility, and social change.

“You can’t be Black without being political. Same with being gay. Just kissing your girlfriend is political. ACT UP was a pivotal time in my life. I was too young to participate in the civil rights movement. ACT UP gave me the chance to put my body on the streets and to photograph. I went with the flow of the demonstration, sometimes I was a photographer, sometimes I was a demonstrator. I have always felt like I was an activist, like Angela Davis.

The AIDS crisis brought us together as a family. That was a time when guys and girls started working together. It galvanized us. The year I graduated college in 1981 was the first year someone was diagnosed with AIDS. I felt like I had to do this work. I vowed never to take a beautiful picture-like a flower- until the AIDS crisis was over.”

— Lola Flash in an interview with Kate Walter for Senior Planet

Their early photographic practice using cross-colour slide film was itself a political statement. By inverting colors and altering conventional representations, they drew attention to the constructedness of photographic “reality,” particularly as it relates to race, skin tone, and beauty standards. This reclaiming and reimagining of representation was a form of resistance against dominant visual tropes that erased or flattened marginalized identities.

Over time, Flash’s activism took many forms: community portraiture, archival photography, exhibitions, mentorship, teaching, and institution-building. Through series like SALT, LEGENDS, [sur]passing, and more recently syzygy, the vision, Lola preserves and honors narratives of survival, aging, Black and queer identity, and futurity. For Flash, the camera is a tool not just for capturing a moment, but for rewriting histories, affirming identities, and projecting alternative futures.