Introduction

LJ Roberts stands at the vibrant juncture of craft and queer identity. Their practice—rooted in knitting, embroidery, collage, and artist books—is a conscious reclaiming of materials traditionally relegated to the domestic sphere, transforming them into sites of radical presence. The Queer Houses of Brooklyn…, a sprawling patchwork installation, spells out layers of home, kinship, and protest in every stitch. Yet what gets woven in each loop is more than geography—it’s a fabric of queer visibility that refuses invisibility.

“Seeing art with queer content helped me understand myself when I had no vocabulary or visual images that spoke to how I was feeling where I grew up, a conservative suburb of Detroit. I often tell a story about being at an all girls boarding school and going to Washington DC to see the AIDS quilt displayed in its entirety for the last time when I was 15. Of course it was profound and terrifying to see the devastation and scope of the epidemic, but it was also the first time I saw a lexicography of queer symbols. I bought a T-shirt and that was my first piece of ephemera that I considered LGBT, though we know AIDS doesn’t only affect queer people.

When I look at work by Catherine Opie, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Harmony Hammond, and many others, I am more able to understand myself and the world. Zanele Muholi, the South African photographer calls her work, mostly portraits of Black South African Lesbians who often face terrible violence, “visual activism.” I think this is a really good example of using images to bring politics to the forefront.”

— LJ Roberts in an interview with Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Educated in English, studio art, textiles, and visual-critical studies, Roberts isn’t merely making craft objects—they are articulating a language that blends fibers and theory. Their tenure at Parsons and contributions to critical craft literature situate their work not just in the gallery, but in the archive, classroom, and embodied theory. For Roberts, making is thinking, and stitch is discourse.

Their accolades—from the White House “Champions of Change” award to exhibitions across the Brooklyn Museum, Barbican, MAD, and Smithsonian—though significant, aren’t the work’s endpoint; they’re markers of the cultural shift Roberts is stitching through craftivism. Each show, each portrait, each map writes back against erasure.

This narrative explores how Roberts’s art gestures outward and inward—placing queer history atop public consciousness while weaving intimacy, solidarity, and resilience into everyday action. It’s a trajectory of stitch, story, and sustained solidarity.

Early Life and Background

Cultural and Personal Influences

Suburban Detroit in the 1980s shaped Roberts in uncompromising ways. Learning to knit with their grandmother at age seven introduced a thread that unraveled over decades, tethering them to both tradition and transformation. Their early embrace of queerness—“dykey, angry, rebellious”—met with silencing forces: boarding schools meant to suppress it, and a Jewish body in spaces hostile to difference.

“My maternal grandmother taught me to knit when I was seven. She painted and worked in textiles both figuratively and abstractly. She also studied art history, politics, and psychology in a time when women didn’t have a whole lot of access to those fields. Teaching me how to knit was a technique passed down the generations in her family.

I stopped knitting soon after she taught me, frustrated by my lack of coordination. I picked it back up in college at the University of Vermont. I was an English major studying critical literary theory and poetry, but took sculpture classes on the side. I injured myself severely my junior year and couldn’t access the woodshop, video editing lab, or other facilities I typically went to make sculpture. My solution to complete assignments was to try and knit them. The first project I brought to critique was dismissed by a student who called it “craft.” My professor brilliantly tied working in textiles to issues of gender, race, labor, class, amateurism, and other hierarchies that marginalize people. These issues and their intersections were what I studied in my English classes. When I realized the potential of material to communicate political views and identity, it was very powerful and lit a fire under me.”

— LJ Roberts in an interview with Bowdoin College Museum of Art

At fifteen, Roberts saw the AIDS Memorial Quilt in D.C., encountering public grief and queer activism woven into fabric. That encounter wasn’t academic—it was catalytic. It connected personal precarity with collective mourning, presence with absence. It taught them that textile can be testament.

Detroit’s industrial grit and New York’s queer vibrancy created an unexpected harmony. One informs their resilience; the other, their vision. Double marginality became double fuel: craft reflects their position at the margins, and queering craft becomes a political strategy—mirroring and manifesting queer survival.

Growing up estranged from heteronormative family structures, LJ found themselves seeking kin outside inherited lines. That searching became a lifelong mode—both in art and life.

Early Exposure to Art and Education

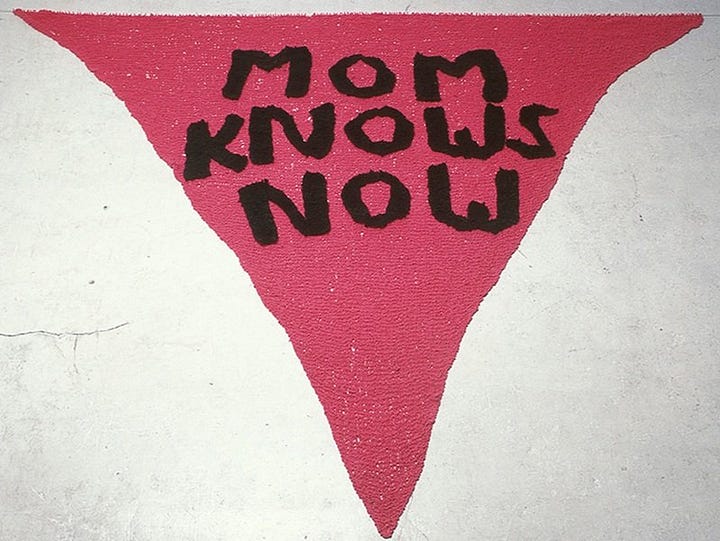

During their college years at the University of Vermont, Roberts suffered a severe injury that disrupted their physical art practice. In response, they turned to knitting—and found a new form of voice in yarn and stitch. That period produced their first activist work: a pink triangular banner reading “Mom Knows Now,” dropped from the campus church steeple in 2003—a gesture of personal coming-out and political alignment with ACT UP aesthetics.

“All of this was happening circa 2000-2002. I was struggling with my gender and sexuality and became involved in the queer activist group at college, which was small but very mighty. The campus was politically charged with a lot of opposing views on LGBTQI rights at the time; civil unions were being voted on and there was controversy about letting the Red Cross have blood drives on campus due to their discrimination towards men who have sex with men. I was also acutely aware of the on-going AIDS crisis and was concentrating on youth access to HIV education and prevention for a class I was taking.

I was also living in a radical environmental cooperative with friends who engaged in civil disobedience such as banner drops to protest deforestation and genetic engineering. I would tag along and photograph them. Around this time I did my own banner drop—I knitted a huge pink triangle appliqued with the text “Mom Knows Now” and hung it without permission to the chapel steeple on campus.”

— LJ Roberts in an interview with Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Working in sculpture and critical literary theory, LJ united academic inquiry with material practice. An early critique dismissed knitting as mere “craft.” Yet, guided by professors who linked textiles to gender, race, and labor hierarchies, Roberts recognized the subversive potential embedded in fiber work. This fusion ignited their career: craft as critique, yarn as argument.

At California College of the Arts, they staged another emblematic intervention—knitting “& Crafts” onto signage after the institution dropped “Crafts” from its name. The work, eventually acquired by Oakland Museum of California, denounced craft erasure in academic contexts and cemented Roberts’s emerging presence as a craftivist artist.

It was during this intense period of study that LJ embraced craft’s portability: knitting on subways, in studios, in classrooms. Materials became mobile, fragmentary, and present. Their education instilled the ethos that textile art needs no dedicated space—it asserts itself in every environment where community and care are possible.

Artistic Influences and Style

Key Influences

Roberts’ work draws on queer theory, AIDS activism, and the material legacy of queer communities. They acknowledge José Esteban Muñoz’s Disidentifications as a guiding text; knit becomes language, and material subversion becomes queer grammar.

Their embrace of “material deviance”—using Barbie knitting machines, toy devices, sock looms—reflects queer strategy: take what is marketed for others (gendered markets), and refashion it for unruly ends. It’s craft as reclaiming both tool and status.

AIDS activist aesthetics—hot-pink triangles, collective structures of the AIDS quilt, ACT UP iconography—are embedded in their work, especially The Queer Houses…, which transposes quilt logic into cartographic form.

Their academic practice reinforces this. Teaching at Parsons and contributing essays in Extra/Ordinary and Craftivism cements their role in evolving craft discourse—not as decorative, but political, intersectional, and scholarly jewel in fiber.

Art + Identity

Roberts’s work deeply entwines technique with identity. Knitting’s elastic structure becomes a metaphor for queer fluidity—stretchable, responsive, resisting static definition.

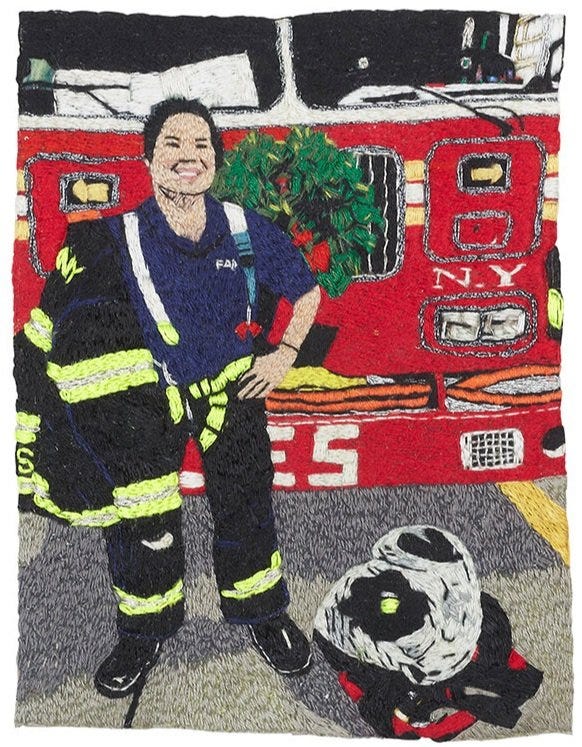

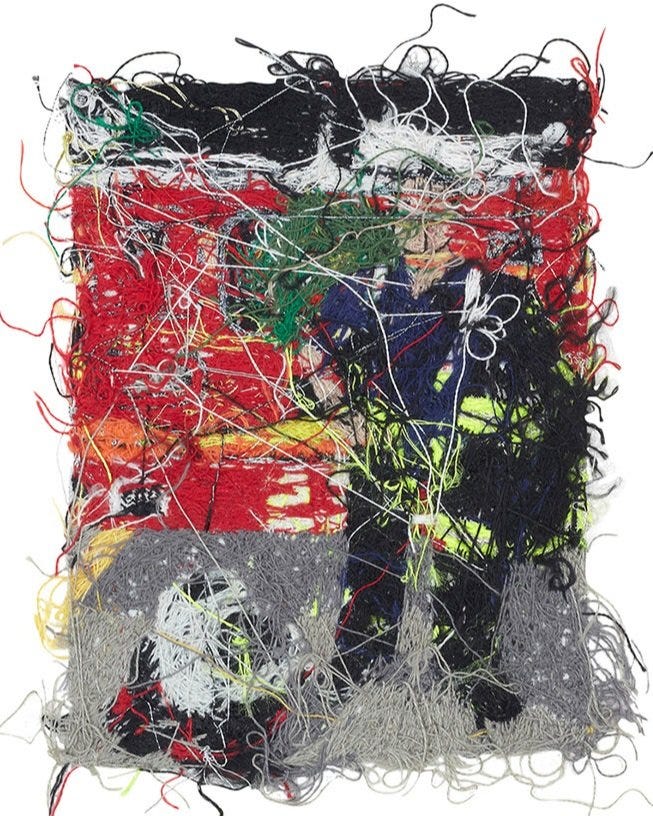

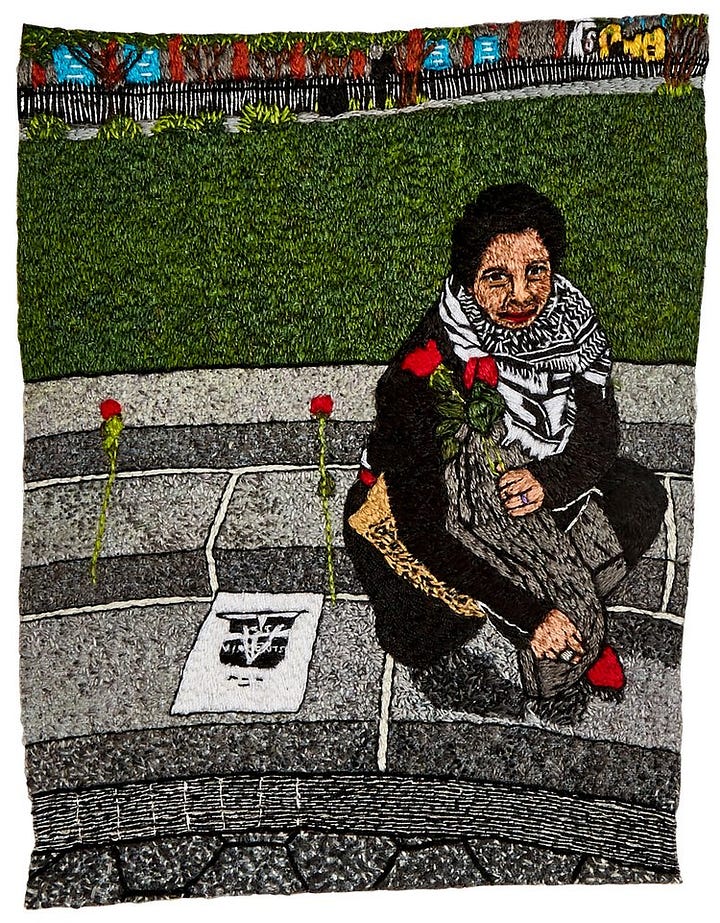

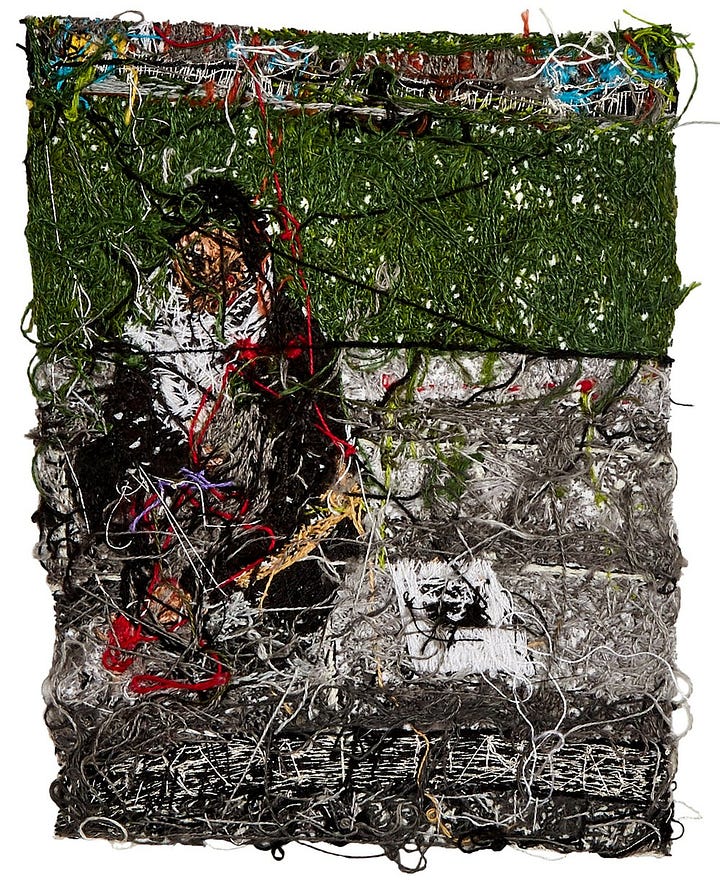

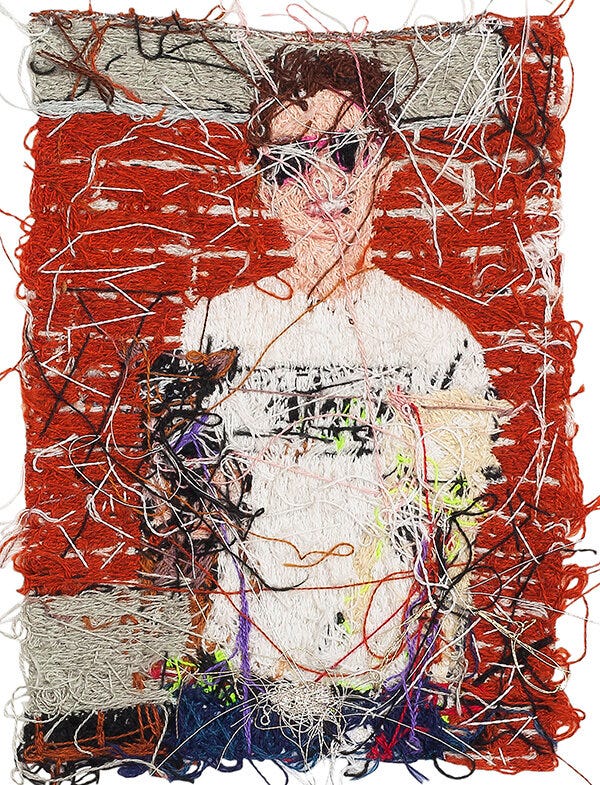

In Carry You With Me, they created 26 small subway-stitched portraits of chosen kin. The decision to show both front and back emphasizes that identity is construable, layered—full of hidden knots and struggling stitches. This makes the labor visible, and identity tactile.

“I pay no attention to what manifests on the back of the image, and its outcome is entirely incidental. Yet the abstraction is just as important as the figures, maybe even more so because it captures the essence of my friends”

— LJ Roberts in an interview with The New York Times

These portrait works aren’t just inclusions—they’re invitations. They say “Your face, your life, your presence matters—so I will stitch it, carry it.” The travelability of work mirrors queer migration and visibility patterns.

Roberts intentionally foregrounds tangle, misalignment, and unpolished edges—rejecting craft perfection to affirm queerness as process, not product.

Art + Activism

Roberts isn’t interested in making work about politics—they want art that is politics. Their pieces assert that politicizing craft isn’t optional—it’s essential.

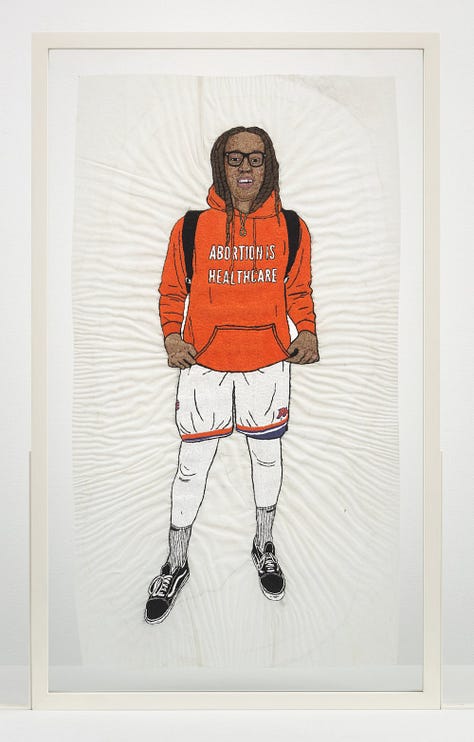

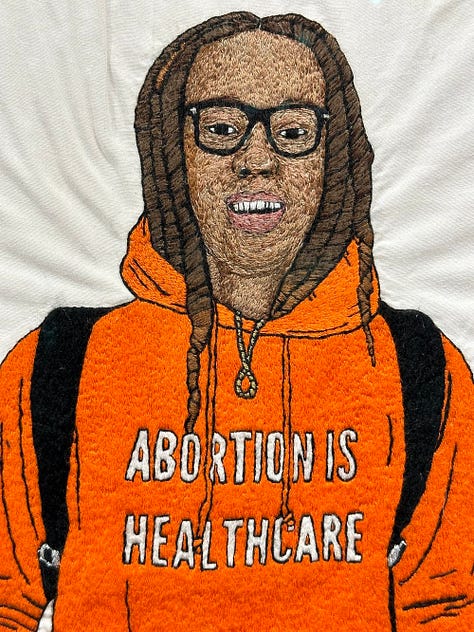

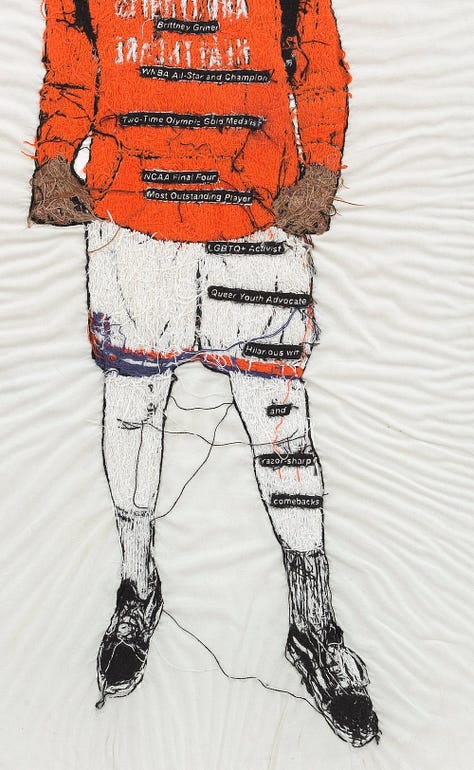

LJ Roberts’ textile-based practice often brings visibility to queer and trans histories that have been overlooked, suppressed, or deliberately erased. In their embroidery depicting Brittney Griner, Roberts expands this mission to include contemporary political struggles that intersect with queer identity on a global scale. Griner’s unjust imprisonment in Russia, a country known for its harsh anti-LGBTQ+ policies, was not only a geopolitical flashpoint but also a deeply personal crisis for the queer community. By depicting Griner in thread, Roberts both honors her resilience and confronts the broader systems of surveillance, control, and marginalization that queer and trans individuals continue to face worldwide. The act of stitching becomes a form of protest and preservation, threading together solidarity, memory, and resistance.

The Knitted Van at MAD (2017) signals not just memory of Van Dykes lesbian travelers, but reflects ongoing queer nomadism in face of environmental/economic precarity.

“I think imagining what seems like impossible societal structures that have less violence than the reality of the current ones is useful for thinking through the activist actions. I don’t think we need to leave the Earth to imagine the possibilities of a just and safer world. I like the tactics of harm reduction, and dismantling stigmas that are applied to marginalized people. It seems logical by now that we would understand that criminalizing people who have HIV/AIDS is not only unproductive but inhumane. It seems entirely achievable to me. Black Lives Matter has provided a real time model of how to foster sustainable movements. I find the most rewarding activism I engage in involves collaborating with people who are very different than me. I like to be challenged to think bigger, to want more, and to work towards that.”

— LJ Roberts in an interview with Allure

And every stitch is relational—made with consideration, care, and connection. Craftivism, as a quiet long-term form of protest, becomes visible—and Roberts is both weaver and witness.

“This piece was a really critical launch pad into art histories I wasn’t taught in the classroom and eventually connected me with people, mostly in New York, who were doing direct actions and queer activism to advocate for people living with HIV. It also taught me about the accessibility of textiles, which is also a very important part of my practice.

…

When I was given this archive of Deb’s it immediately struck me as a portrait of her based in a specific time and place. This is ephemera from her life and activism during a devastating time. We saw the AIDS crisis decimating marginalized populations, climate change, war, austerity, culture wars, and mass incarceration heighten during this specific time and they continue. Deb’s “stuff” shows the intertwined politics and activism she was involved in.

This felt important to acknowledge because at the time I received the collection and began stitching the piece there was a lot of cultural production, exhibitions, and film that revisited the AIDS crisis in the late ’80s and early to mid ’90s, the time period that Deb’s collection spans. Much of this production concentrated on the narratives of cisgendered white gay men. Deb’s collection shows how feminism, trans and lesbian identities, anti-racist politics, fat activism, and reproductive justice among other issues were critical to the fight against AIDS. There are also many strategies of activism illustrated from humor, to militancy, to public grief, to calls for action. Using embroidery spoke to feminist legacies of art making and activism that were integral during this time.”

— LJ Roberts discussing Portrait of Deb in an interview with Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pride Palette to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.