Introduction

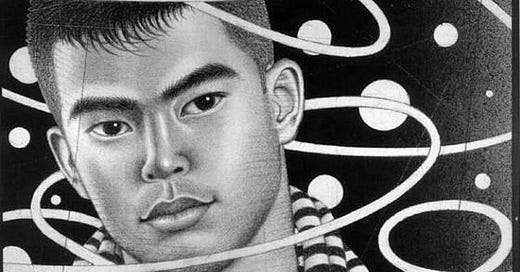

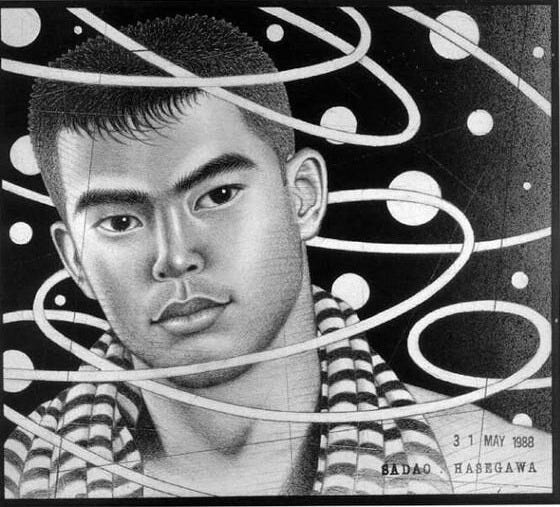

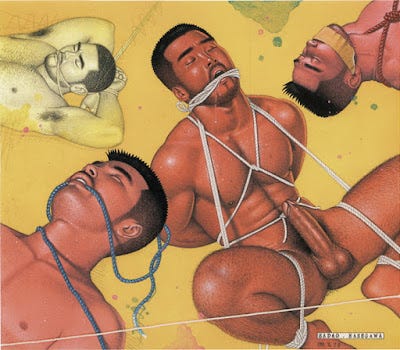

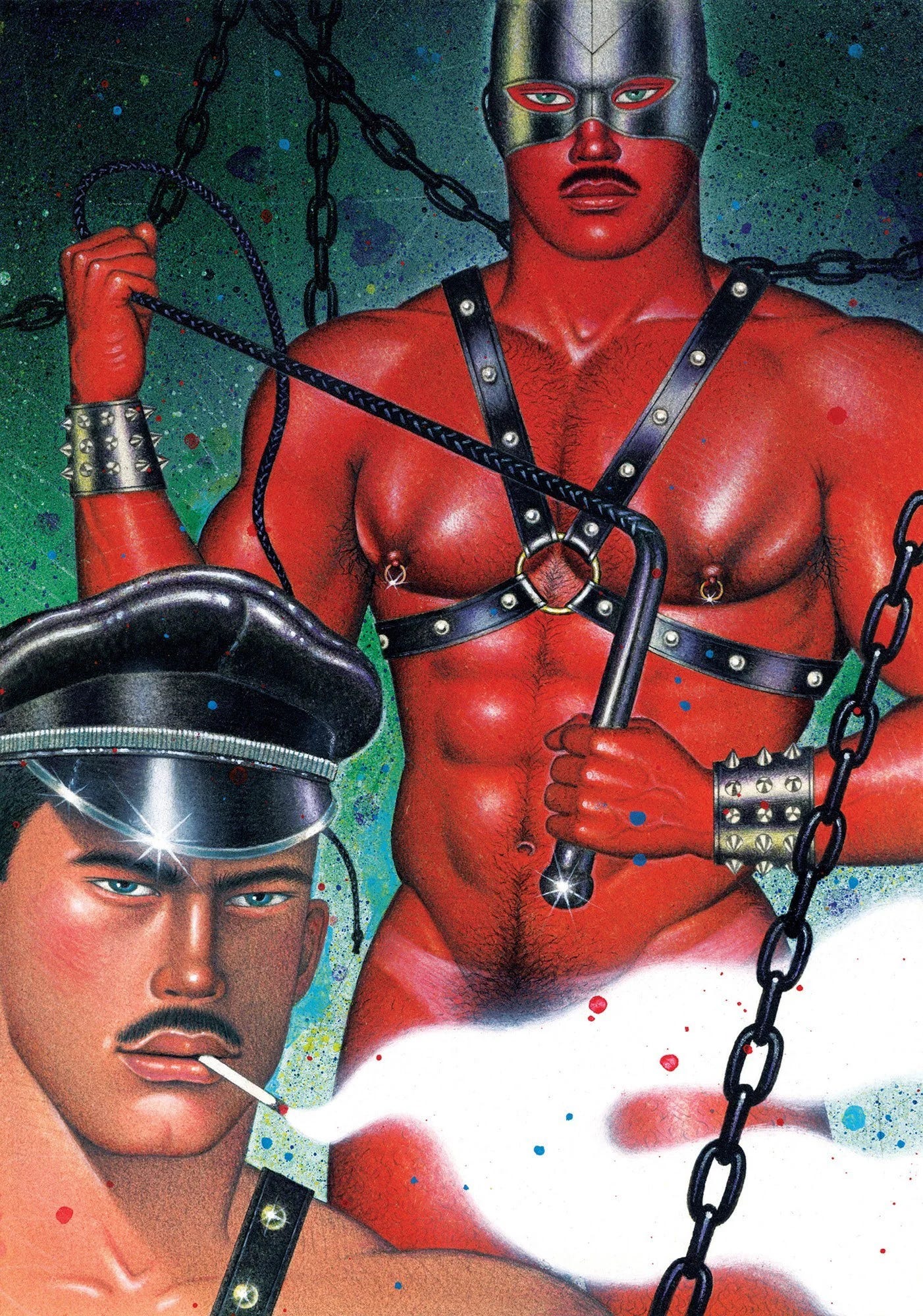

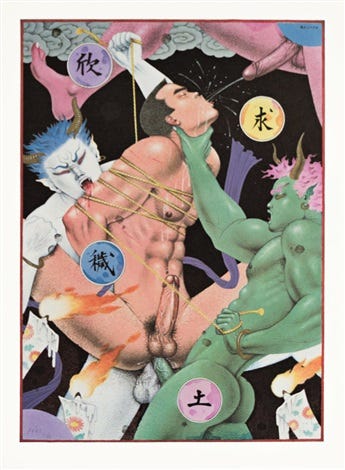

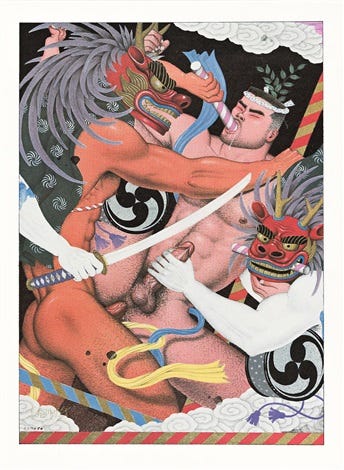

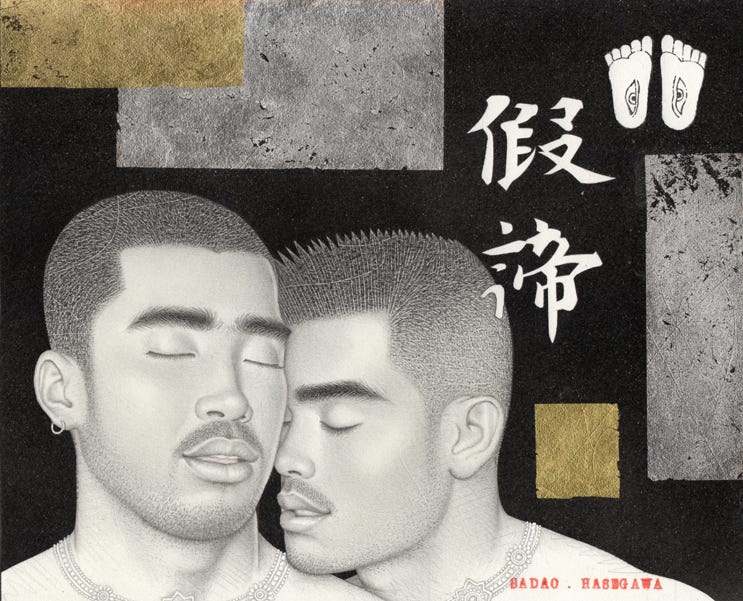

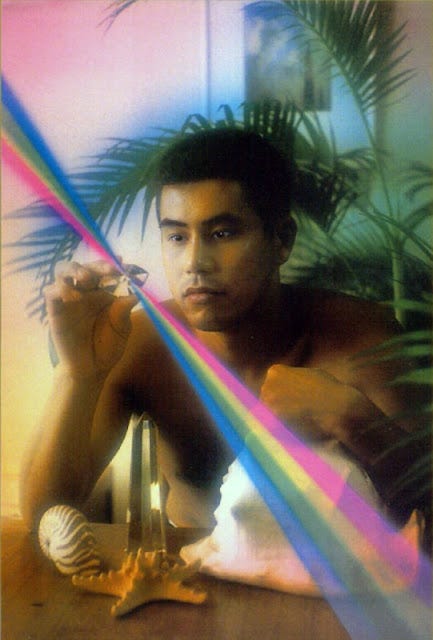

Sadao Hasegawa (1945–1999) was an autistic, Japanese graphic artist whose beautifully intricate homoerotic illustrations melded muscular male forms with mysticism, bondage, and a rich tapestry of Asian mythologies. Born in Japan’s Tōkai region, he began creating art in his twenties, culminating in his first solo show, Alchemism: Meditation (1973), in Tokyo. Though his work included highly explicit themes—bondage, sadomasochism, and fetish elements—it transcended eroticism through spiritual gravitas and a devotional rendering of the male body.

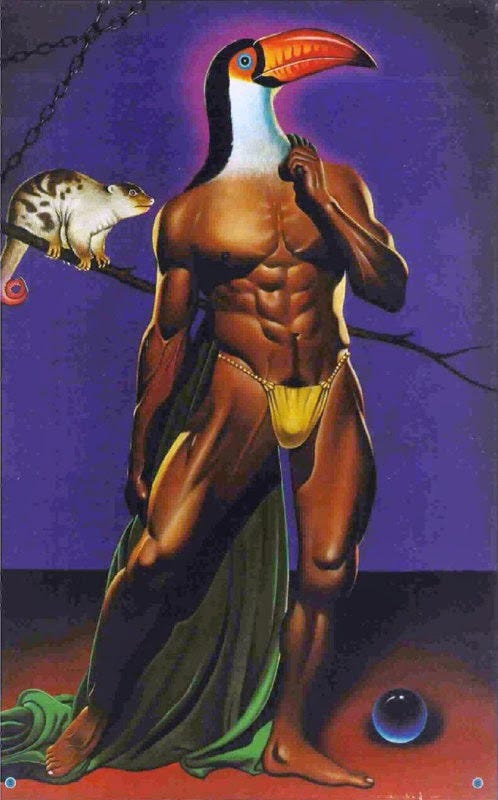

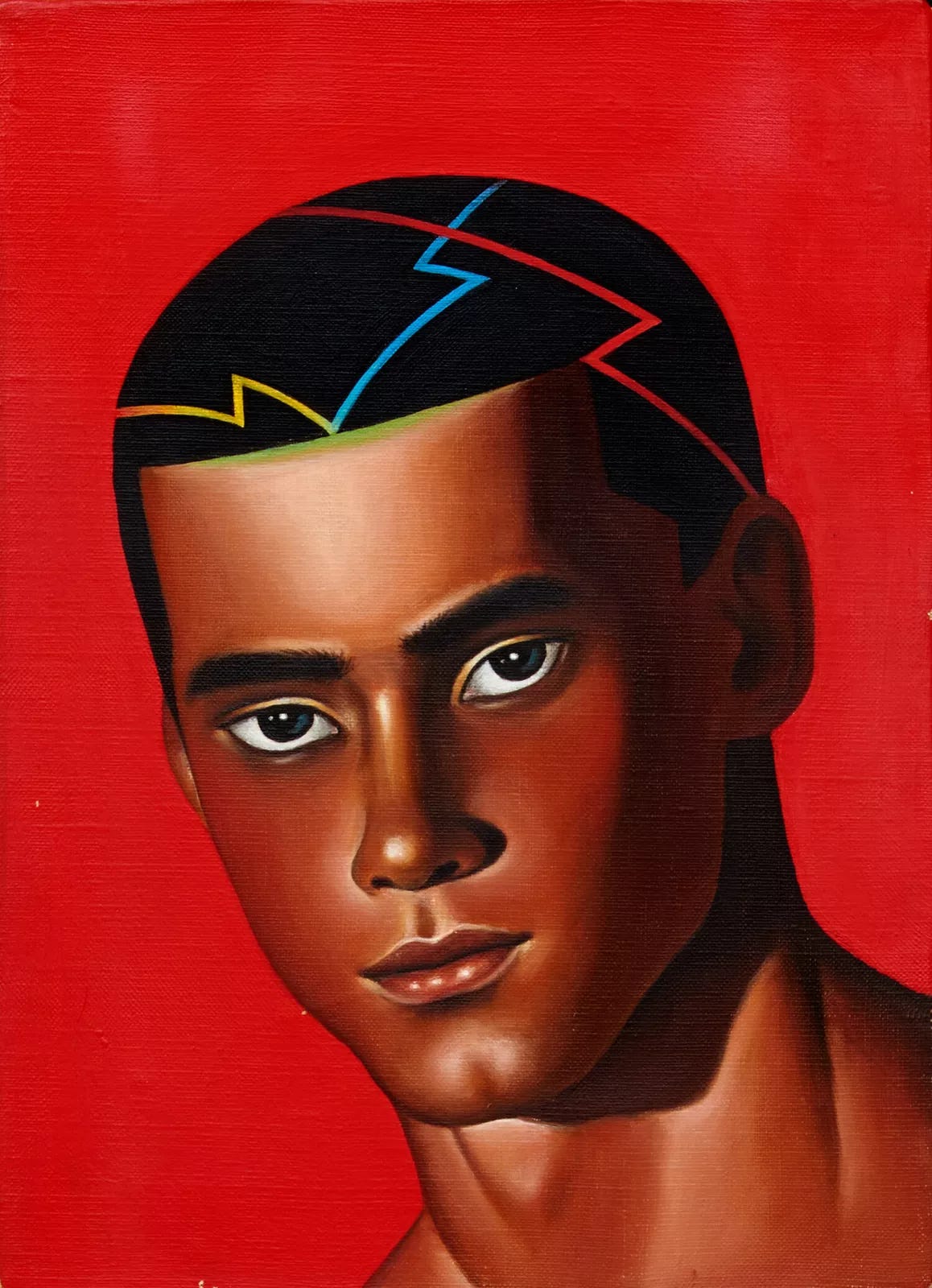

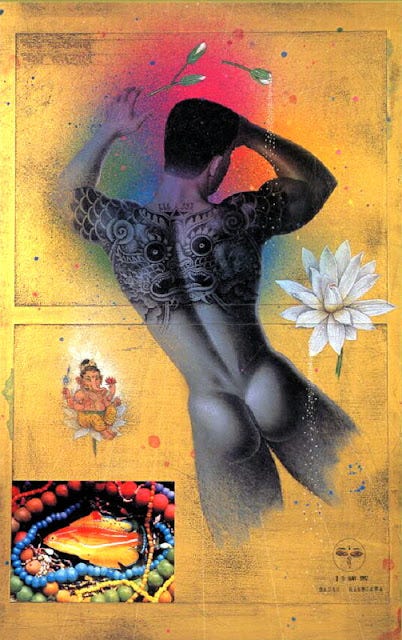

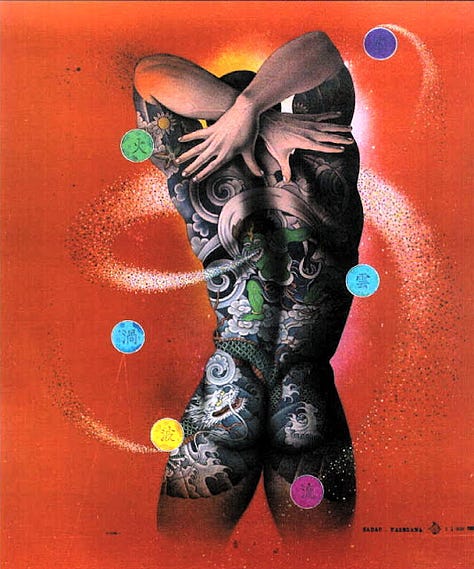

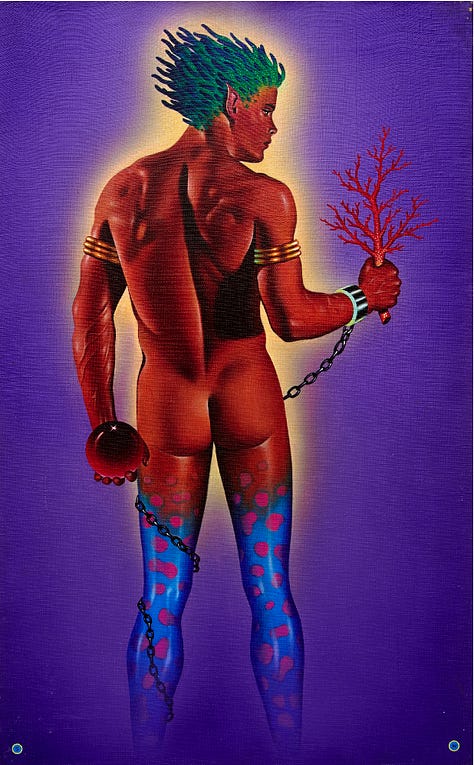

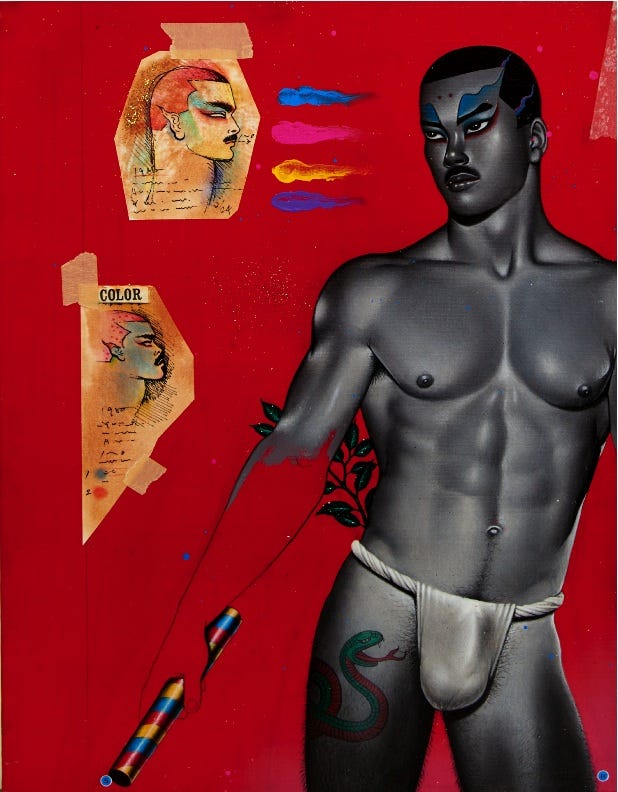

His aesthetic drew deeply from Southeast Asian cultures—Thai, Balinese, Tibetan, Indian—and African motifs, fusing them into surreal landscapes populated by hyper-masculine figures adorned with symbolic ritual markings. These were more than erotic fantasies: they were visual hymns steeped in Buddhist symbolism, lotus thrones, and ascetic iconography.

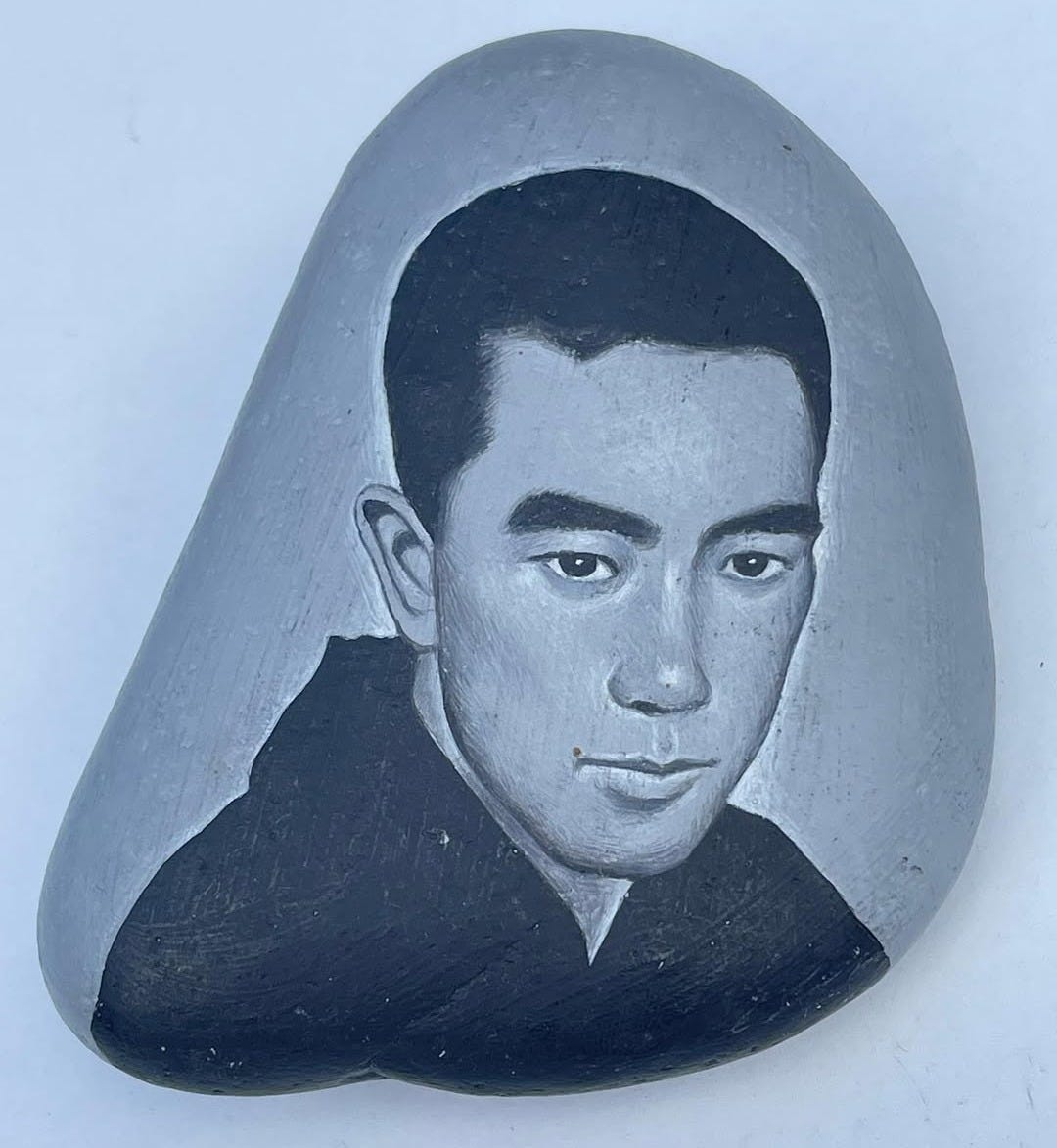

Despite offers to exhibit abroad, Hasegawa chose a quiet, introspective path, keeping his work largely within Japanese queer publications—Barazoku, Sabu, Samson, Adon—and refusing substantial international exposure. He tragically died by suicide in Bangkok on November 20, 1999, echoing the demise of Yukio Mishima, to whom he left a painted stone portrait of and a note entrusting his art to Tokyo’s Gallery Naruyama, ensuring its preservation. Right after Sadao died, his family originally found his art and trashed it. It wasn’t until they found his note and the stone that they retrieved his works and honored his wishes, thus preserving his works for years to come.

Early Life and Background

Cultural and Personal Influences

Born into postwar Japan in 1945, Sadao came of age during rapid societal change, yet gravitated toward introspection. Self-taught, he said he “took up drawing in his twenties,” which eventually led to his first Tokyo exhibition in 1973 . Early on, he idolized Go Mishima and Tom of Finland—Mishima for his powerful male imagery, and Finland for his stylized European erotic art. In fact, he penned a memorial for Mishima in Barazoku, calling him “a master illustrator of the male physique.”

Hasegawa’s early style mirrored these Eurocentric influences: taut, fetishistic, and intimate. But as his travels began in the late ’70s—to India, Bali, Thailand—his palette expanded into Southeast Asia’s iconography and mythologies. Over time, his renderings became saturated with tantric symbols, ritual ceiling, decorative patterns, lotus thrones, and dark spiritual nuance.

His identity emerged at the intersection of queer desire, ritual art, and spiritual invocation. He carved a unique space: drawing from queer eroticism, layering it with spiritual gravitas, and setting it against a broad multi-cultural backdrop. Sadao’s refusal to conform to a conventional art world pathway reinforced his personal ethos: create for self, not for fame.

Early Exposure to Art and Education

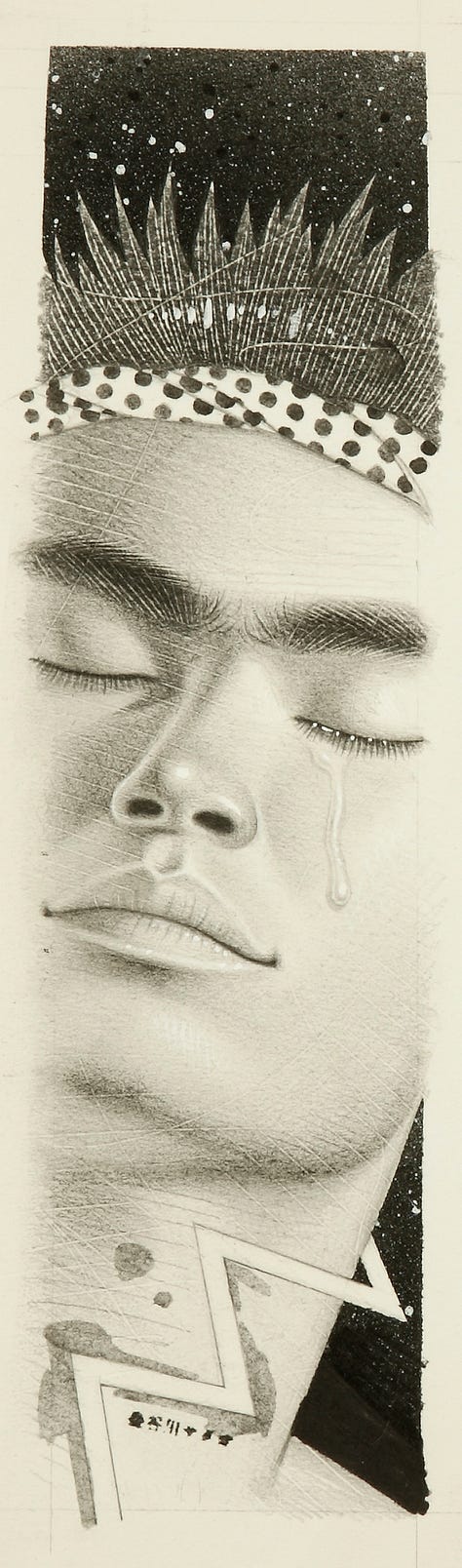

Without formal artistic training, Hasegawa discovered art through travel and magazines. His 1973 exhibition featured oil painting, sculpture, and collages, showing his versatility and conceptual depth. His entry into Barazoku in 1978 marked a new phase: public acceptance in Japan’s gay media and visual culture.

It was through such publications and personal journeys that he absorbed Eastern aesthetics—learning traditional ornamentation, Buddhist iconography, and the mysticism of Tantric and Shamanic symbolism. His travels were not passive; they were homework, spiritual immersion, and aesthetic research.

In his later years, this unconventional education bore fruit in works that place muscular figures in ritualistic poses: floating, bound, or isolated in cloud-like, psychotropic landscapes. His renderings cross cultural boundaries, yet each line is informed by meticulous observation—impasto gouache strokes, detailed ink, gouache, and pencil layering . Sadao’s art was self-education in motion—ever-reinventing.

Artistic Influences and Style

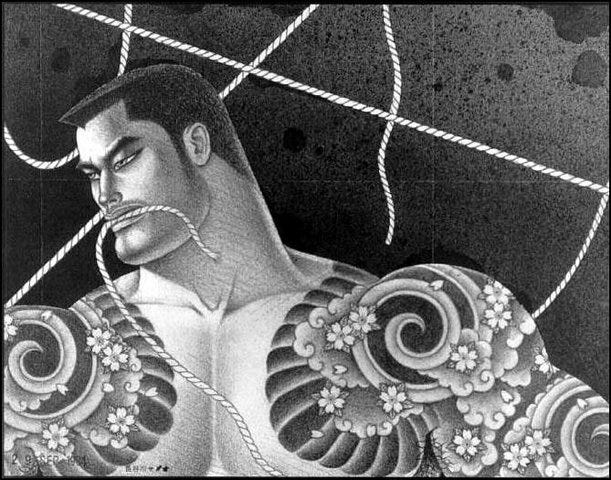

Key Influences

From the outset, Hasegawa’s work was shaped by his predecessors. Tom of Finland’s hyperreal male form and fetish playstyle are clearly visible in his early works. Meanwhile, Japanese artist and illustrator Go Mishima’s classical musculature and tattooed spiritual warriors profoundly affected his aesthetic; Sadao explicitly revered Mishima in print.

The years he spent in Bali and Thailand are peaks in his creative timeline—adding Buddhist lotus thrones, ascetic figures, tantric symbolism, and Southeast Asian decor into his erotic compositions. He blended these with elements from Tibet, India, and Africa, weaving a cross-continental tapestry of myth: shamans, gods, tattoo motifs, and spiritual geometry .

These influences merged into a surreal, ritual-fetish style that was unmistakably Hasegawa. His figures—often nude, always strong—were embedded in larger metaphysical tableaux, as if ritual dancers in a hidden cabal, bound to gods, spirits, or mythic beasts.

Art + Identity

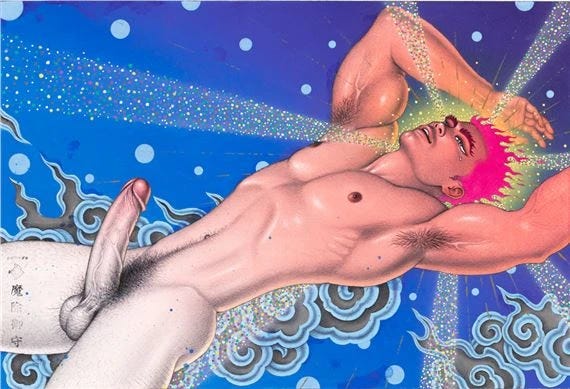

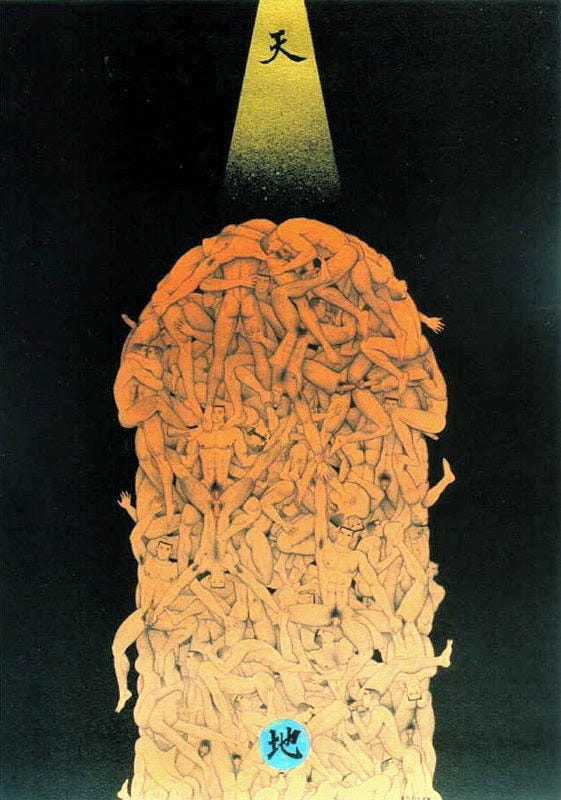

Sadao’s work is an unapologetic exploration of gay desire. He celebrates gay identity as something sacred, not secret, by placing queer bodies in mythic landscapes and spiritual allegory. He positioned the queer male form as a vessel of the divine: lotus-throned ascetics, suffering yet exalted bodies, tortured into transcendence.

Erotic images—bondage, ropes, penetration—are rendered as ascetic acts: bodies in suspension, offering, ritualized suffering and ecstasy, linking sexual submission with spiritual ascent.

He doesn’t sanitize the kink; instead, by embedding it within spiritual iconography, he declares queer sex as a legitimate path to self-realization. There’s no shame here—only sacralized embodiment.

He transmuted queer identity from marginal sexual fantasy into spiritual complexity. Each piece asserts that homosexual desire can be sacred and powerful, worthy of ritual reverence—and not secondary to heterosexual or religious norms .

Retaining the explicitness of fetish art, Hasegawa elevated it with mythic and ascetic allegory. These were not crude erotic prints—they were explorations of martyrdom, ecstasy, discipline, and devotion, with queer bodies at their spiritual center.

Art + Activism

Hasegawa’s art was radical in stance, though not overtly political. In 1970s–90s Japan, queer art existed on the margins—but by publishing consistently in gay magazines and refusing mainstream appropriation, Sadao enacted soft activism.

By depicting gay men across cultures and epochs—with icons that suggested connections to Asia’s spiritual traditions—he implicitly challenged Western tropes. His aesthetic refusal to conform to Eurocentric stereotypes or submissive roles represented a form of queer assertion.

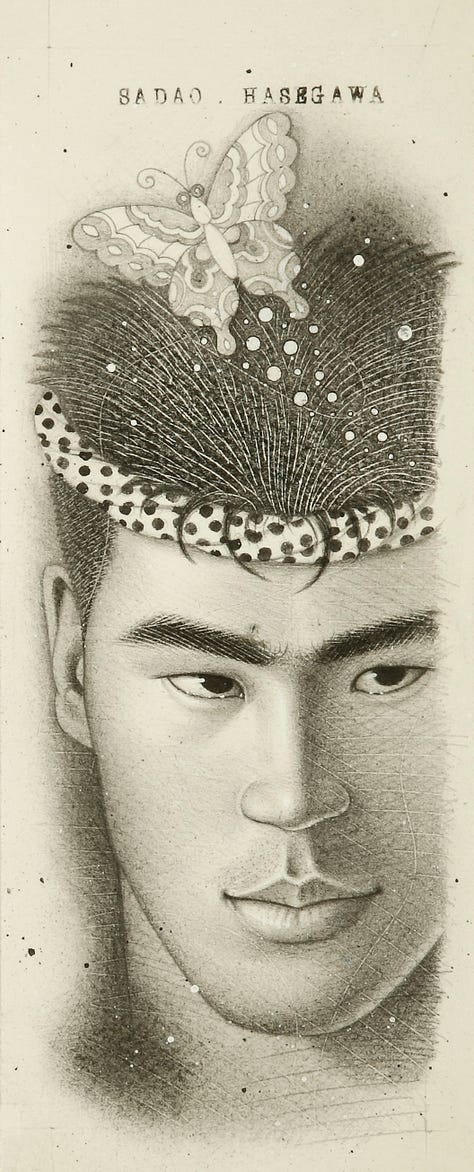

Due to the sale of his prints through the Tom of Finland Foundation's then-president, Durk Dehner, Hasegawa's works were known to audiences outside Japan via only reproductions. He declined various invitations to exhibit abroad, fearful that his drawings and paintings would never make it back through Japanese customs. In 1995, Sadao wrote to Durk Dehner of the Tom of Finland’s Foundation, with the following note:

“Born in 1950. Tell you the truth, I have never had formal training of art.

I was kind of an autistic child who could not enjoy playing with other kids at all, rather, it was even painful for me.

Instead, communing with mother nature, loving flower, animals, and tiny insects were my mentor.

It was my supreme happiness when I indulged in reveries, fantasies, and my own paintings.

Although I acquired sociability in my later years, my habit to ‘trip’, to communicate with super-nature still remained and it has become part of the most important source of my inspiration.

My past motif have been Grecian, Indian, Egyptian, Japanese Kabuki, folklore, and Buddhism.

Now I’m enthusiastic about Indonesian and Thai religious motif.

I have strong interest in Asian men, religion, sense of beauty.

My desire is to create the universe of beauty of men, in a way which differs from Western point of view.

Especially these days, I try to pursuit spiritual, profound beauty and eros rather than a pornographic worlds which is something like furious orgies or sadism and masochism.

I have had exhibitions several times in Japan. Unfortunately, no museums has my work in their collections.

Japanese society is still very conservative and museums are not ready to exhibit Gay art yet.

My work is now published every month on the ‘BARAZOKU’, Japanese gay magazine. This year, a plan is on foot to publish a book of selective pencil-drawings from BARAZOKU.

I travel to Indonesia 3 or 4 times a year, [gaining] new ideas from an cultural exchange between local boys.”— Sadao Hasegawa in a letter to Durk Dehner, 13 February 1995

Within Japanese queer circles, his repeated publication contributed to visibility—helping define gay aesthetic in print media when public spaces remained restrictive .

By merging eroticism and spirituality, he confronted both queer community and cultural conservatism—demanding that erotic desires be taken seriously, non-judgmentally, even reverentially.

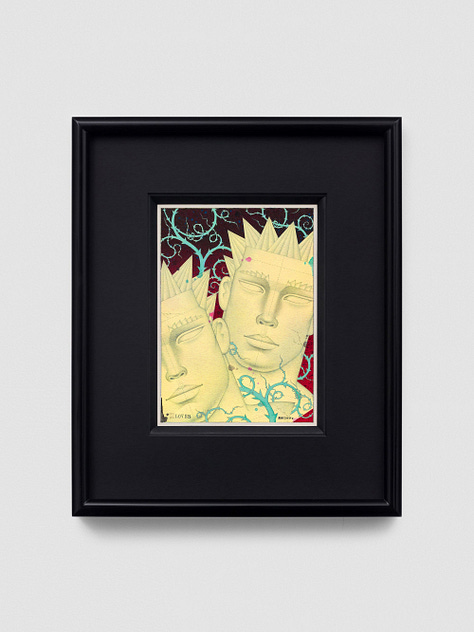

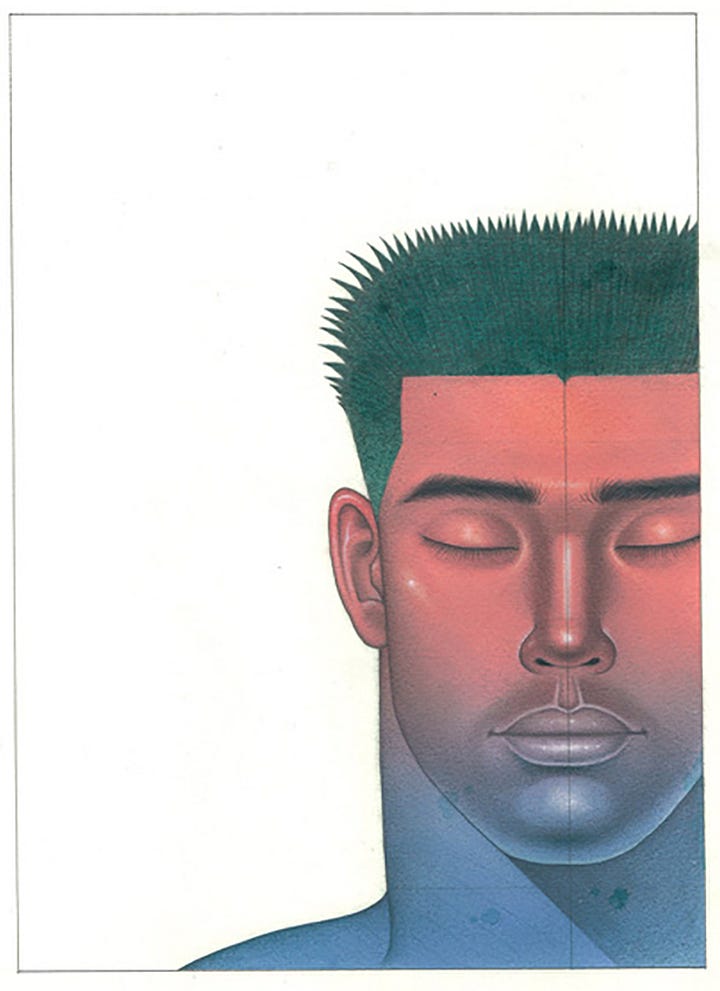

Significant Works

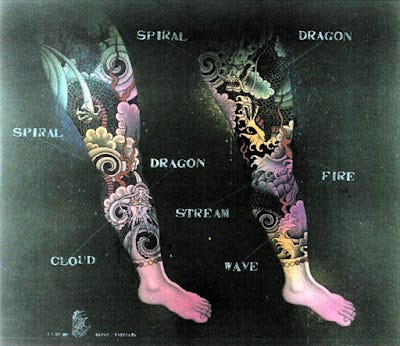

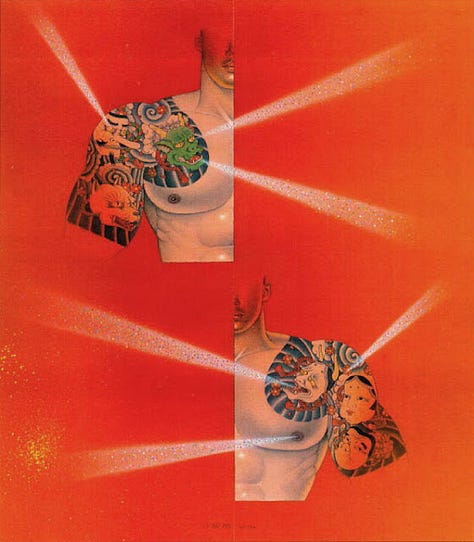

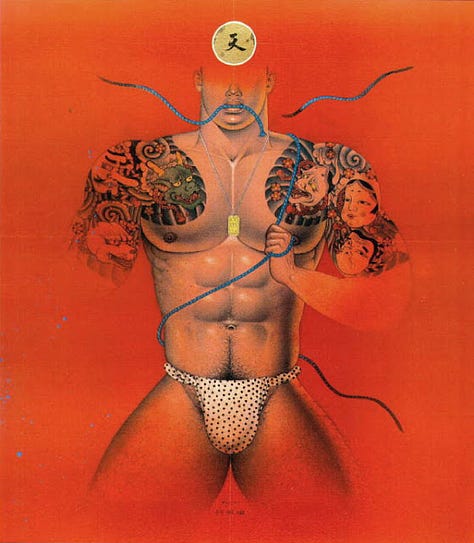

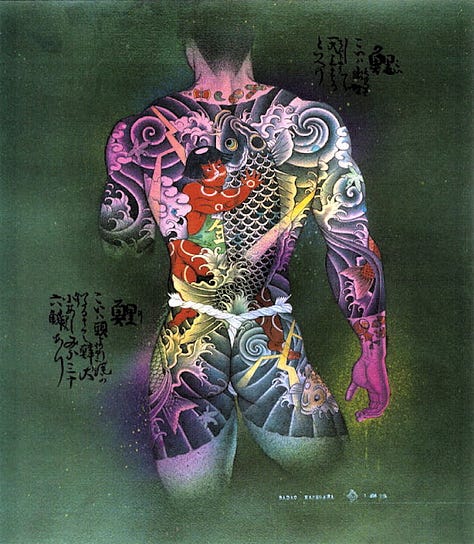

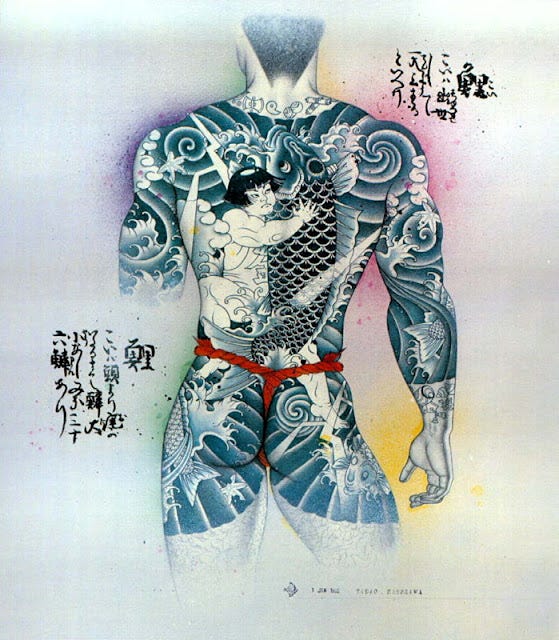

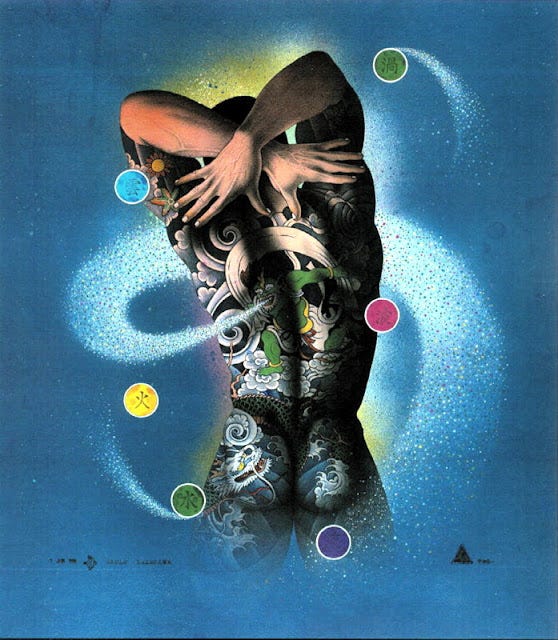

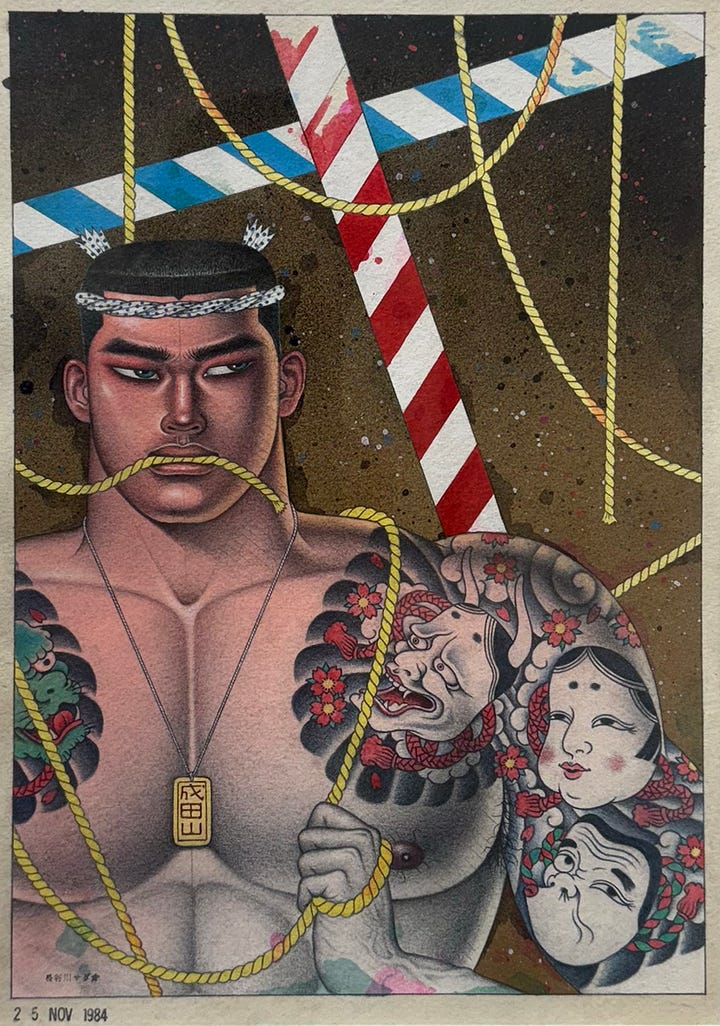

Tattoo Series, 1980-1989

In Sadao Hasegawa’s Tattoo Series, the body becomes a sacred canvas, richly inscribed with mythic motifs and fetish fervor. Influenced by the bold inkwork of Go Mishima’s tattooed yakuza men, Sadao’s designs breathe new life into the erotic—merging S&M symbolism with Asian spiritual symbology .

The series reflects Hasegawa’s deep affinity for Southeast Asian heritage. Lotus mandalas, ritual masks, tantric symbols, and cosmic geometries—elements he gathered in Bali, Thailand, and India—are transformed into corporeal ornamentation. The tattoos are not ornamental but talismanic, each pattern a gateway to discipline, devotion, or inner divinity.

By rendering these powerful images as tattoos, Sadao declared that queer flesh, discipline, and devotion are interwoven. These artworks challenge the viewer to see beyond erotic allure, recognizing queer bodies as living embodiments of ritual, resistance, and sacred lineage.

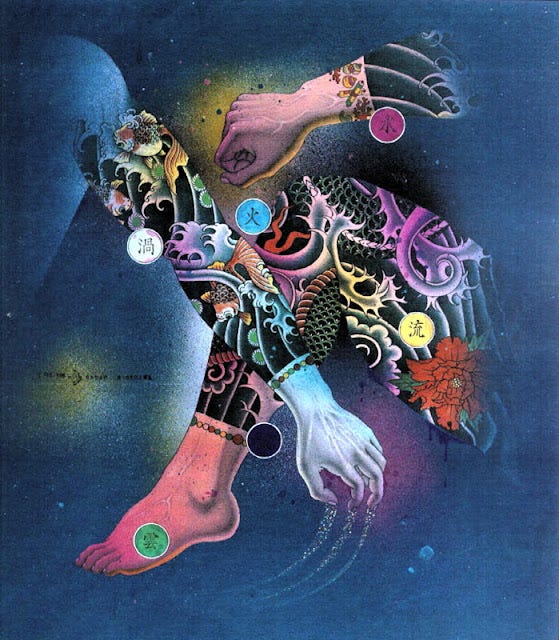

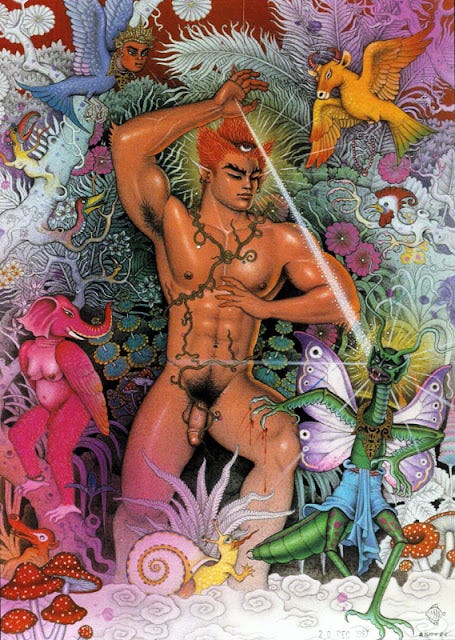

Secret Ritual, 1987

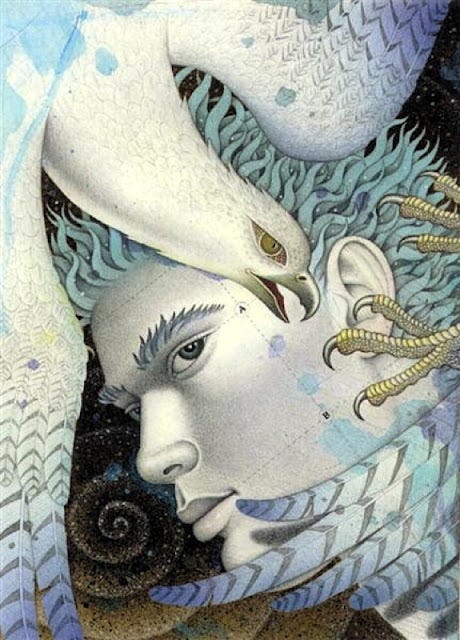

In Secret Ritual, Sadao Hasegawa conjures a mystical world where the boundaries between body, spirit, and myth dissolve. The painting immerses the viewer in a kaleidoscopic realm of otherworldly creatures, tantric symbols, and lush, surreal patterns that swirl around a serene male figure. There’s no sense of danger or domination—instead, the composition hums with sacred stillness. The man at the center seems to float in spiritual rapture, as if mid-ritual or dreaming within a temple of the cosmos.

This work reflects Hasegawa’s deep engagement with Eastern metaphysics and queer spiritual embodiment. Drawing from Thai, Balinese, and Hindu iconography, he populates the canvas with protective spirits, hybrid beasts, and celestial energies. The “ritual” here is not one of physical ordeal, but of inner awakening—a trance-like state where self and surroundings are in perfect alignment. In Secret Ritual, Sadao envisions queer masculinity not as taboo, but as divine.

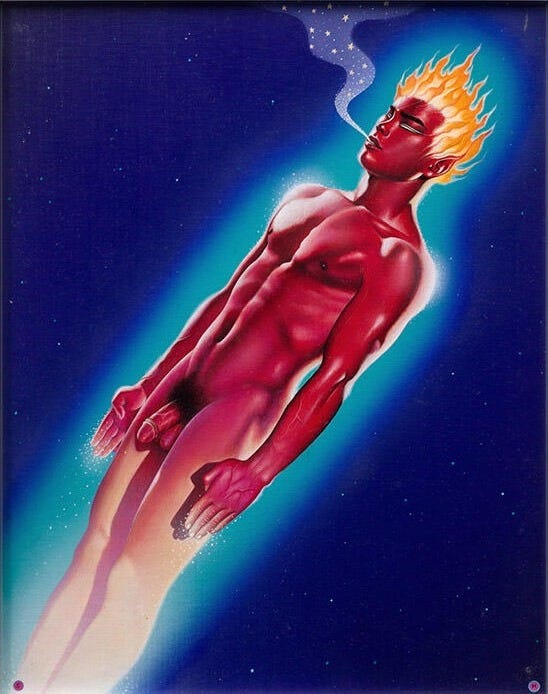

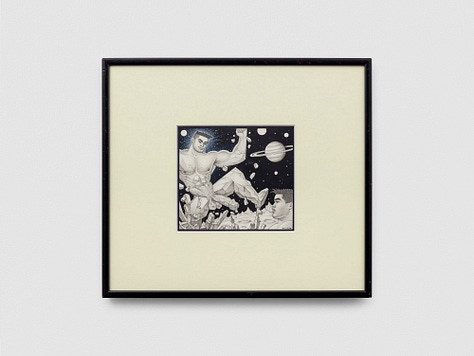

That Floating Feeling, 1980

That Floating Feeling (1980) features a naked man sleeping or meditating in a celestial haze, a jewel between his eyebrows resembling a Buddhist urna, while his crimson skin and flaming hair liken him to Agni, the Hindu god of fire.

In That Floating Feeling, Sadao masterfully captures a surreal sense of weightlessness, portraying a muscular figure suspended in space—neither bound nor free—evoking the meditative drift between flesh and spirit. This atmospheric reverie draws deeply on the artist’s explorations in Southeast Asia, channeling Buddhist notions of transcendence and unmoored consciousness. The body becomes a vessel of contemplation, adrift in an ethereal realm that blurs the boundaries between erosion and elevation.

This piece reflects a turn in Hasegawa’s art away from explicit fetishism toward introspective, almost mystical exploration. Here, the erotic merges with the transcendent: flesh meets void, and the viewer is invited to share in a moment where spirit ascends beyond physical confines—an emotional evocation of peace that floats between worlds.

Acclaimed for their craftsmanship, these works stand as major milestones in queer erotic art—they defined a uniquely Japanese synthesis of sex and spirituality. Though never exhibited internationally during his life, these works circulated in queer magazines like Barazoku and Sabu, proliferating his vision in the 1980s–90s Japanese gay underground. They remain the benchmarks of his lasting legacy.

Recent/Upcoming Exhibitions

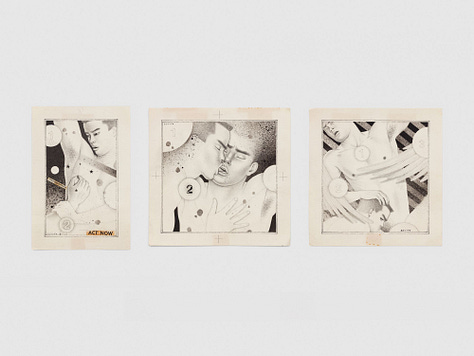

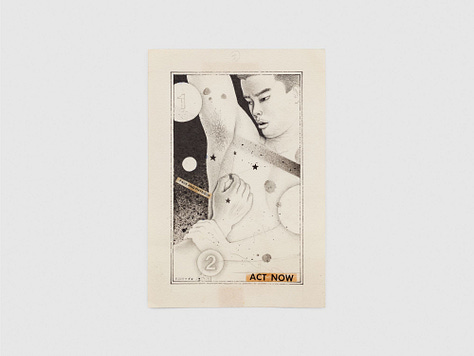

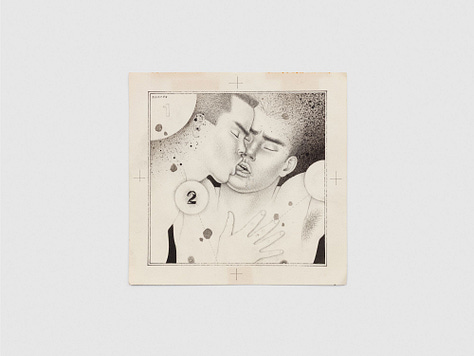

Sadao Hasegawa: English Companion Inc. - a. SQUIRE - London, UK (Mar 8, 2025 - Apr 26, 2025)

a. SQUIRE hosted an exhibition of works on paper by Sadao Hasegawa (長谷川 サダオ), English Companion Inc., which was organized in collaboration with Gallery Naruyama, Tokyo. This is the only solo exhibition to happen outside Japan and the first presentation of his work in the UK.

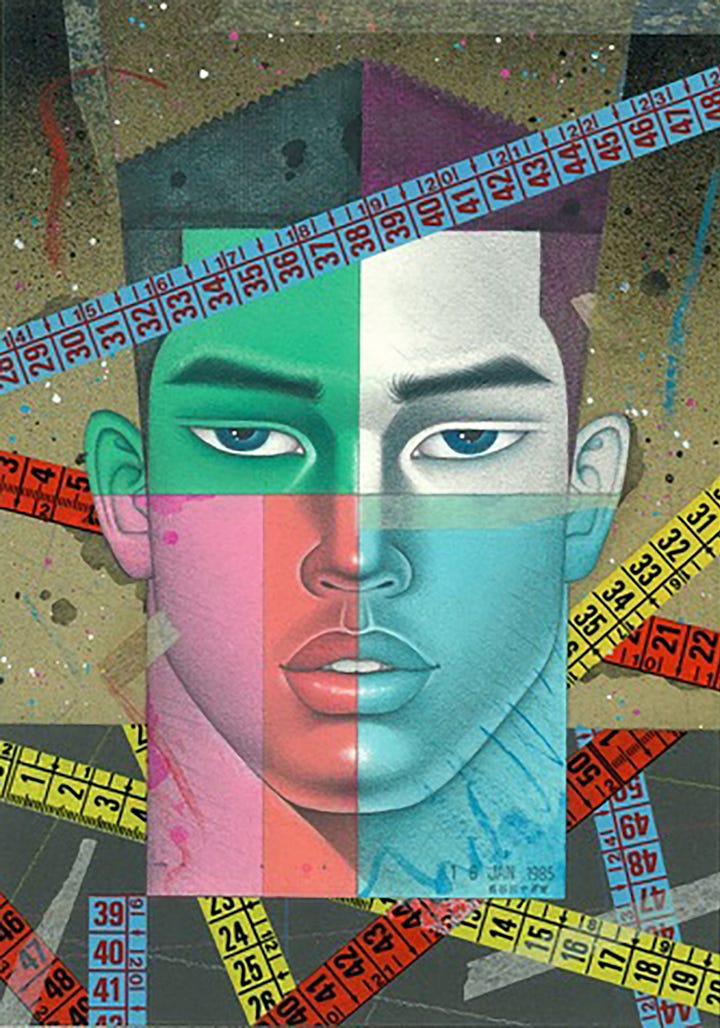

How to introduce Hasegawa's dazzling universe for the uninitiated? It is starry-eyed and joyous and tender, richly sensual and brimming with fecundity. A hallucinogenic realm of priapic gods and demi-gods, shibari and romance, it is unfettered in its adoration of Asian men's bodies, and in its holism and attention to all living beings, imparts a Buddhist sensibility. It is supremely skillfully rendered, a dissertation in modulation and Day-Glo colours.

He lived in Tokyo, longed to travel to India, and in 1978 began working regularly with publisher Itō Bungaku, who seven years earlier had founded the first commercial gay magazine in Japan, Barazoku (薔薇族). During the earlier half of the 80s, Sadao’s work gained fast attention domestically, illustrating the pages and covers of Sabu (さぶ), The Adon (アドン), and Samson (月刊サムソン). It was around this time, too, that his images started to appear in gay publications in the West, among them In Touch for Men [I.T.] and Mach (a Drummer title).

"In Bangkok's National Museum, when the guards were not looking, Sadao liked to touch the large stone sculptures of Khmer and Hindu deities, 'for their power'," recalled his friend, the late Berkeley professor Frits Staal. Hasegawa began making frequent trips to Indonesia and Thailand in the 1980s, and with these his syncretic vision of Asia emerged. It was not only a guiding superstructure but also constituted a politics of its own. In his works, Balinese cult pools with Hindu iconography, Thai mythoi and Confucian legend interweave on a seamless plane.

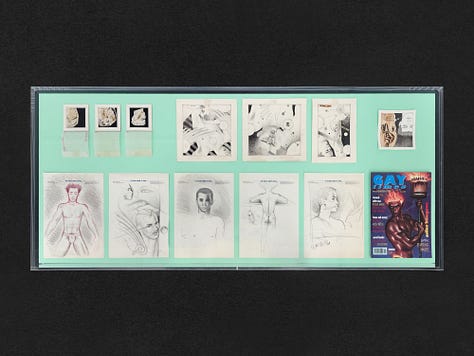

Sadao Hasegawa: Magazine Cover Original Illustration Exhibition - Gallery Naruyama - Tokyo, Japan (Apr 3, 2025 - Jun 7, 2025)

Since acquiring Sadao Hasegawa’s estate in accordance with his 1999 will, Gallery Naruyama has served as the primary guardian of his oeuvre. Gallery Naruyama has continued to mine his archive with exhibitions highlighting distinct phases of his creative life. The 2014 show 1978–1983 dug deep into his ritualized homoerotic illustrations from the late 1970s, while Winter/Spring curatorial series (2023–24) explored both intimate drawings and spiritual allegories . In 2024, the gallery even partnered with Toga Aoyama to present Sadao Hasegawa 70s, an exhibition bringing early psychedelic and painting works to fresh eyes. In 2025, they hosted the Magazine Cover Original Illustration Exhibition, which showcased some of his magazine cover illustrations.

By continuously exhibiting rare and early pieces—and supporting publications like SADAO HASEGAWA 1945–1999—Gallery Naruyama has both preserved and amplified Hasegawa’s legacy. Their efforts have transformed a once marginal queer-ritual aesthetic into a lasting voice within Japanese and international art dialogues.

Online and Print Recognition - Various Sources (2000 - 2025)

More than two decades after his death, Sadao Hasegawa’s work is undergoing a powerful resurgence. In recent years, international publications such as Frieze, i-D, e-flux, and Emergent Magazine have revisited his bold, ecstatic visions with new urgency—framing him not just as a forgotten master of erotic art, but as a spiritual provocateur ahead of his time. These features explore how his fusion of homoeroticism, Eastern mysticism, and ecstatic figuration makes his work uniquely resonant in a contemporary landscape that continues to wrestle with the intersection of queerness, cultural identity, and spirituality.

Writers and critics have particularly emphasized how radical Sadao was for centering Asian queer men in spiritual and mythological grandeur—at a time when most global representations of queer erotic art were white, Western, and secular. His recent international exhibitions and digital features have introduced his art to younger generations of LGBTQIA2S+ people who see in his work a mirror for their own fluid, spiritual, and proudly non-Western identities. In a 2024 Frieze review of English Companion Inc., his art was described not only as "aesthetic resistance" but also as "a pathway into queer transcendence," affirming that Hasegawa’s mythology remains deeply relevant today.

For many in the Asian queer community, especially those who are reclaiming ancestral belief systems and artistic heritage, Hasegawa’s work offers a vital form of representation. His art doesn't just eroticize—it deifies. It imagines queer desire as sacred, not shameful; as disciplined, not disorderly. This reclamation of queerness through cultural specificity and spiritual richness has found renewed life in contemporary conversations around intersectionality and decolonization. 26 years after his death, Sadao is no longer a quiet figure at the margins of art history—he’s becoming a mythic ancestor of queer Asian futurity.

Reflecting on Sadao’s Journey

Hasegawa’s path from self-taught erotic illustrator to spiritual fetish visionary is remarkable—and it highlights a commitment to queer-sacred integration. Even without academic training, he found mentorship in Mishima, Tom of Finland, travel, and prayerful crafting.

His refusal to commercialize maintained purity of intent—his art was never for mass consumption, but for soulful self-expression and cultural conversation.

His death echoes Mishima’s tragic symbolism, but his final act—donation of his archive—ensured future generations could witness a deeply personal aesthetic worldview.

Today, rediscovery elevates him beyond niche erotica: he sits at the crossroads of queer liberation, ritual studies, and Asian art discourse. His visionary legacy refuses to be contained, continuing to evoke devotion.