Introduction

Pippa Garner’s legacy stands as one of radical transformation—not just of objects, but of the self. A conceptual artist, satirist, inventor, and trans icon, Garner devoted her life to creatively undermining societal conventions, especially those tethered to gender, consumerism, and technology. Her work defies easy categorization, slipping between industrial design, performance, illustration, and text-based provocation with the same fluidity that came to define her gender transition. What began as pranks or thought experiments matured into a deep, lifelong critique of the manufactured self. Her projects were often as absurd as they were insightful, exposing the contradictions embedded in consumerism, identity, and the American dream.

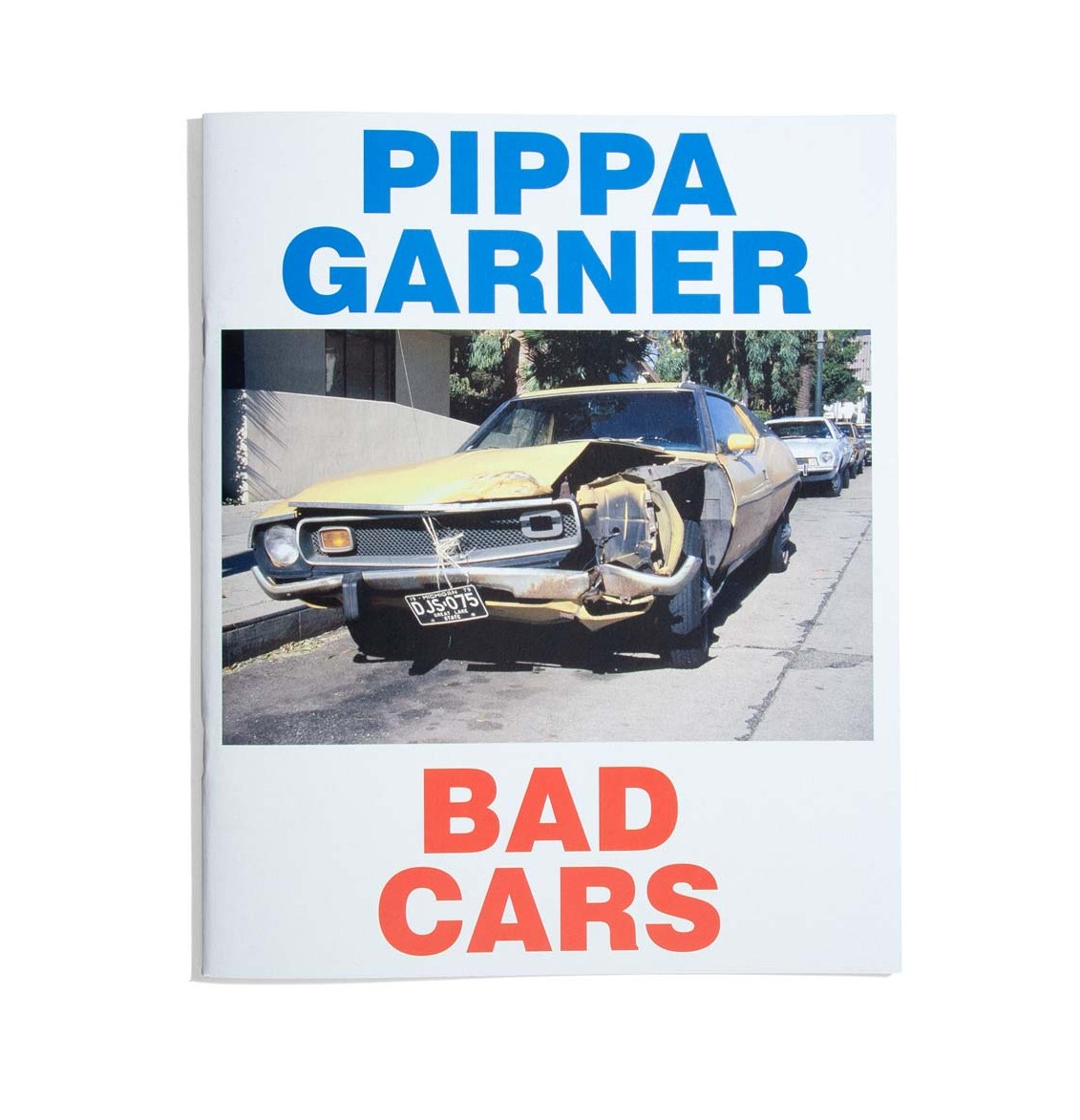

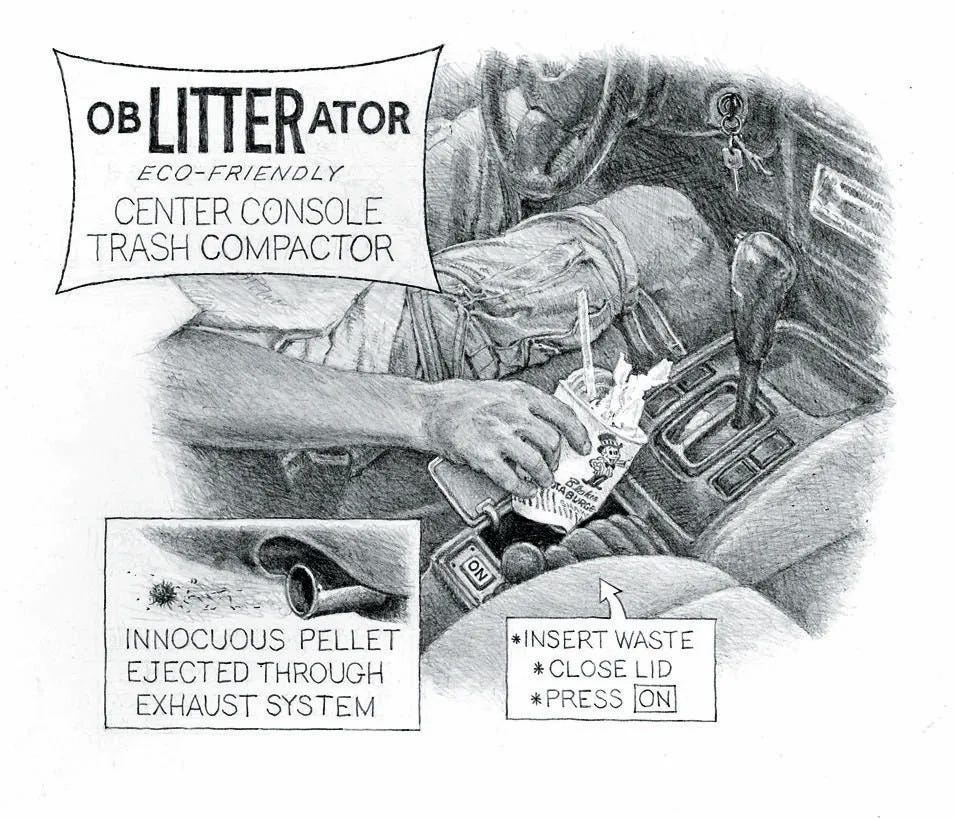

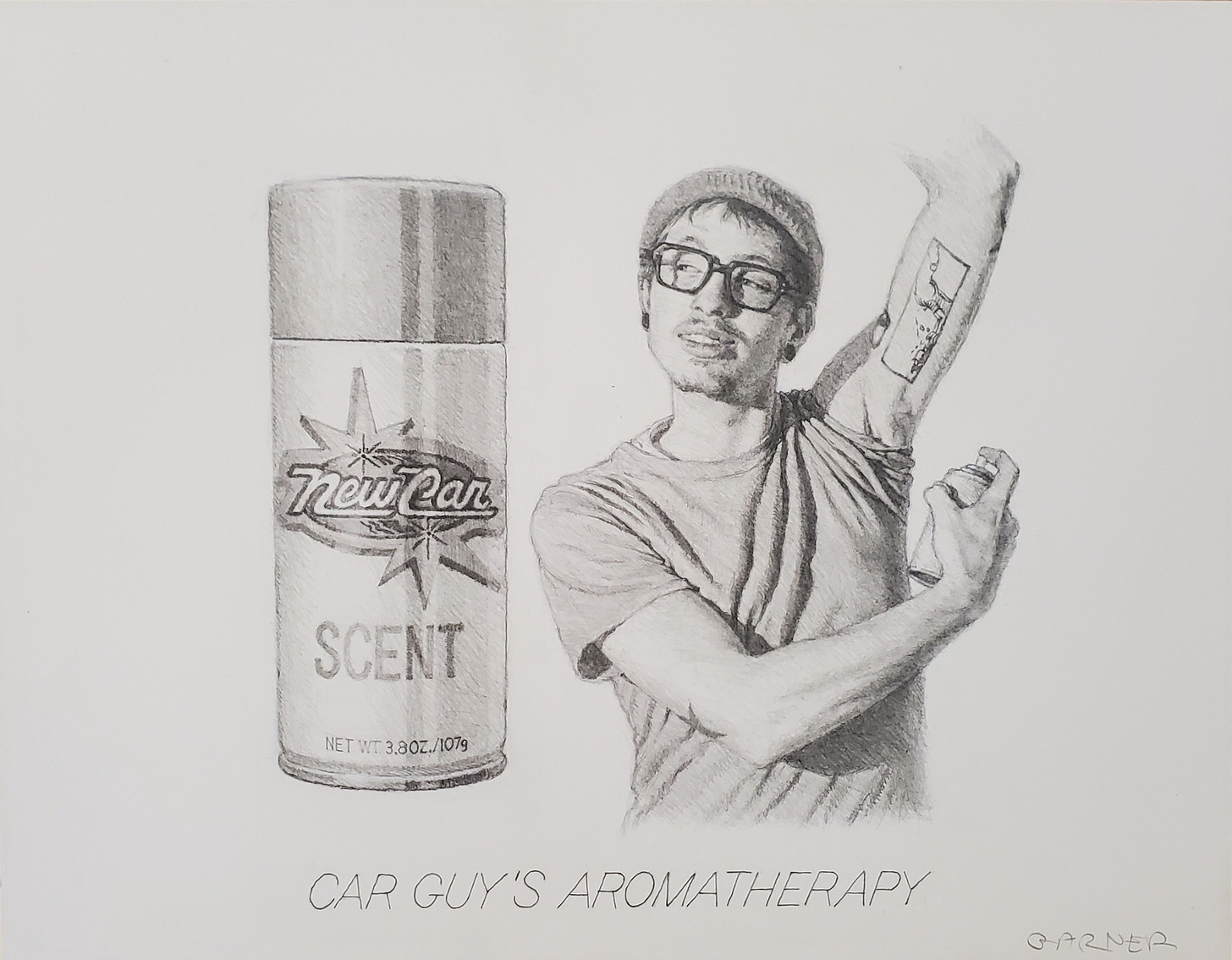

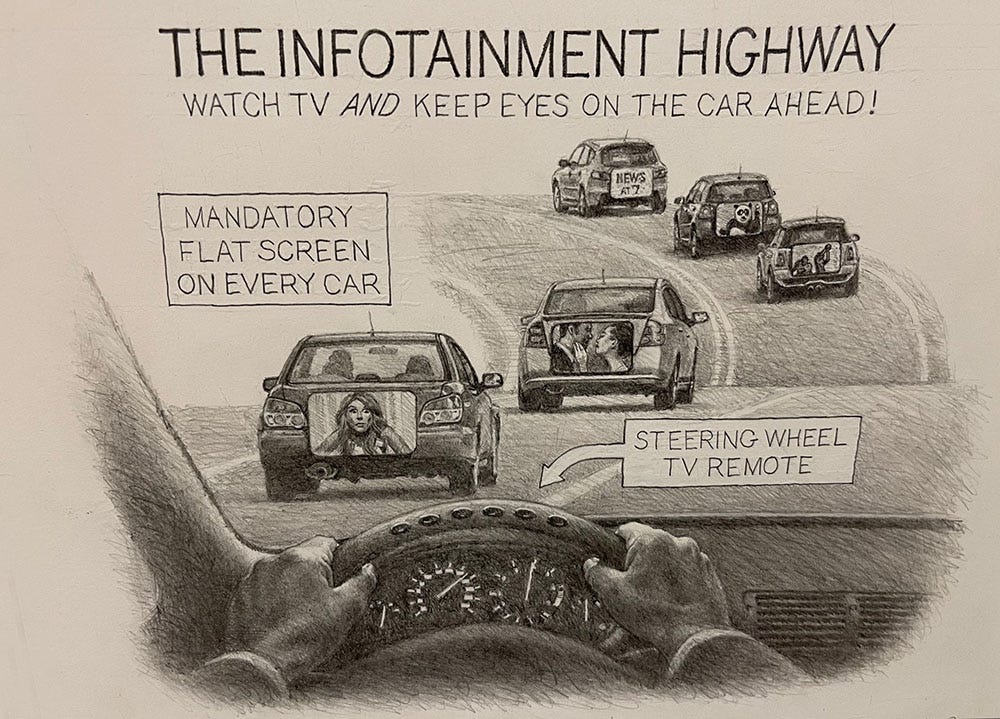

Born in 1942, Pippa lived a life that mirrored the disruptive brilliance of her art. She transformed mundane consumer products into absurdist inventions that laid bare the underlying contradictions of capitalist logic. Whether by redesigning cars to be less functional or imagining products like "Blaster Bra," she exposed the hilarity and harm in society’s obsession with conformity and utility.

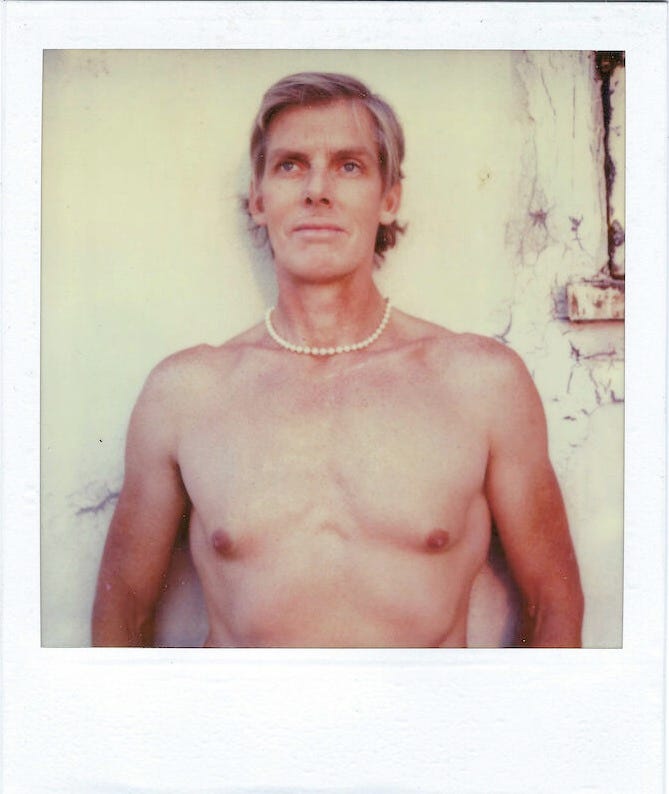

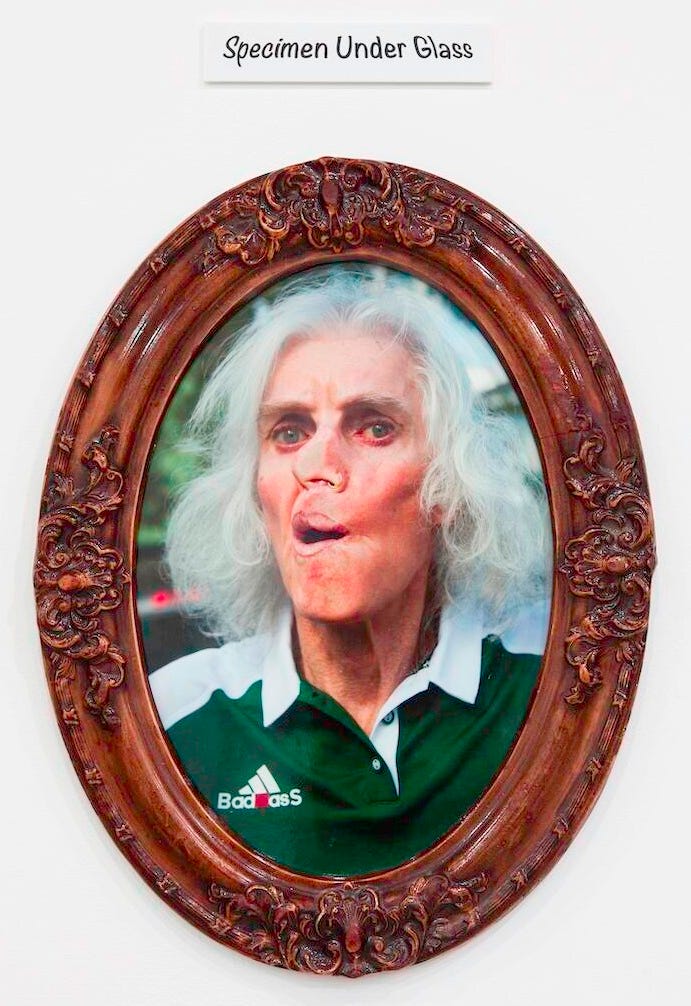

As a transgender person who began her transition in the late 1980s, Pippa’s artistic and personal transformations were deeply entwined. At the heart of her practice was transformation—not just personal, but societal. She referred to her gender transition as a conceptual art piece in itself—a statement that challenged essentialist notions of identity and embraced self-authorship. Her wit and playfulness masked a profound resilience, offering a model for living creatively in defiance of normativity.

In the final decade of her life, Garner experienced a resurgence of recognition. Critics and curators reevaluated her body of work as prescient—seeing in her gender hacking, product mutations, and satirical media interventions a template for the artistic and political urgencies of the 21st century. With her death in 2024 at the age of 82, the art world lost not only a mischievous genius but a vital voice in the conversation around queerness, consumption, and invention.

Early Life and Background

Cultural and Personal Influences

Garner was born in 1942 and raised in Evanston, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago shaped by postwar ideals of consumerism and suburban conformity. She was raised by her mother, whom she characterized as a “frustrated housewife” and her father who sold ads to car companies from Detroit, America’s auto capital. The glossy ads shaped Pippa’s enduring fascination with automobiles at an early age, while her upbringing instilled a complex relationship with mainstream American culture—one of fascination, irony, and quiet rebellion. The son of a businessman, she was immersed in a world obsessed with growth, gadgets, and gender roles. From an early age, Garner viewed these institutions not as fixed realities but as strange performances open to disruption.

“My father worked for McCall’s , a women’s magazine, but I grew up playing with technology and mechanical things. I made my first pedal car with a gas lawnmower engine when I was ten. I became fascinated by automobiles because they had distinct faces. They still have faces, but at that time they smiled, they frowned, they all had expressions. As a small child, if we were driving and saw a bad accident, there might be people bleeding in the street but if I saw the smashed-up face of the car, I’d start crying. That’s a childlike start of seeing consumerism as a strange entity with a life of its own.”

— Pippa Garner, interview with Spike Art Magazine

Pippa was assigned male at birth and came of age in a time that offered little space for gender variance. Her early internal conflicts around gender identity were compounded by the rigid expectations of masculinity, especially in the military-industrial contexts she would later explore in her work.

The Vietnam War had a seismic effect on her artistic direction. Drafted into the U.S. military when she was young, she served as a combat illustrator. This role offered her an unconventional education in visual storytelling and taught her to filter absurdity through documentation. While others engaged in war through violence, Garner witnessed it with a sketchpad—absorbing firsthand the dehumanizing effects of systems too large to comprehend.

“Being a combat artist sounds like it would be some sort of publicity thing but it’s not. The military, going way back, has always had civilians tag along to document what is happening so that they can later gain insight on what went wrong and right, to use in future strategies. When I got to Vietnam, I was looking for a situation that would be interesting and discovered there was a combat art team. I found the officer in charge, did some quick sketches, and they were impressed. I did it for about fourteen months.”

— Pippa Garner, interview with Spike Art Magazine

Post-war life brought her to the West Coast, where counterculture and innovation flourished. Her work as a young illustrator for car magazines and military publications immersed her in visual systems that prized precision and utility. But these same systems became a target of her satire, as she gradually turned those drawing skills toward conceptual subversion rather than obedience.

Throughout her early life, Garner found herself resisting easy classifications—never quite a designer, not merely an artist, and certainly not someone who would comply with conventional masculinity. This resistance would become her trademark, manifesting in a lifetime of deconstructing form and identity.

Early Exposure to Art and Education

Pipa attended ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California, where she studied industrial design. Having moved from Detroit, where her father worked in automotive advertising and the car was revered, she was struck but deeply influenced by hot-rod and custom-car culture.

Even more inspired by automotive absurdities, her irreverent streak took hold. Her senior project—a bizarre hybrid between a car and a human form called Kar-Mann—led to her expulsion, a sign that Garner was always working at the edge of acceptability. Her time at ArtCenter was pivotal: it sharpened her technical skills while also convincing her that mainstream design offered no room for subversion or absurdity.

“Everyone took design so seriously. People were designing taillights as if it were the end of the world. I started making fun of it all. I made this thing that was half-car, half-man. The front part was a typical ’50s-looking car, and then it became this male figure—quite realistically sculpted—lifting his leg on a map of Detroit. That was it for them. They were getting a lot of money from the car industry and didn’t want to see that sort of thing.”

— Pippa Garner, in an interview with Art in America

Despite the institutional rejection, Pippa gained attention in Southern California’s underground art and design circles. She began contributing illustrations to Car and Driver magazine, producing humorous inventions that satirized the automobile industry. These works demonstrated her ability to manipulate symbols of masculinity—like cars—into vehicles for social critique.

Her early design experiments laid the groundwork for a practice that blurred the line between product and parody. From “reverse flow cars” to clothing designed to confuse rather than flatter, Garner saw the world as a design problem in need of reprogramming. For her, tools of mainstream consumption could be hacked to reveal their underlying absurdities.

Pippa’s education, both formal and informal, helped her develop a sensibility that married technical expertise with artistic rebellion. She was deeply influenced by the materials and logic of design, but her subversive instincts led her to reinvent rather than reproduce. Art school may have expelled her, but it couldn’t contain her.

Artistic Influences and Style

Key Influences

Garner drew inspiration from many unlikely sources: product catalogs, instruction manuals, roadside signage, and the absurdity of American consumer culture. She was influenced not by high art in the traditional sense but by everyday objects and the strange behaviors they encouraged. She was deeply affected by the 1960s and ’70s counterculture, particularly the rise of experimental art and media in California. The Dadaist spirit of artists who disrupted conventional meaning resonated with her, but she applied this impulse to consumer technology rather than language or collage.

She didn’t want to destroy culture; she wanted to play with it, like a child dismantling a toy to see how it works. Technological change also shaped her approach. Garner saw machines not as enemies, but as collaborators in performance and transformation. She hacked bicycles, invented wearable machines, and proposed imaginative product hybrids that seemed both useless and visionary. In her hands, technology became satire—and satire became liberation.

Art + Identity

For Pippa Garner, identity was not a fixed fact but a flexible construct—something to be shaped, played with, and ultimately reimagined. This philosophy guided both her art and her transition. She famously described her gender transition as an “art project,” which at once challenged essentialist views and reclaimed authorship over her body. She also described it as “a performance project that would be the ultimate ‘consumer hack’.”

“The body becomes a sort of product. I was working with consumer appliances and products, and I thought, ‘Hey, I’m a product too. I have this whole structure that’s designed to hold up my head—systems and subsystems that seem tuned to each other—and it has a lifespan just like other things. If I’m no different from anything else, if my body is assigned to me for a certain time, why not play with it?'.

…

I wanted to do all these surgeries under local anesthesia, because I wanted to be present and see what was going on and be part of the process. To me, it was like collaborating on a project—though with a surgeon as opposed to an artist. They go in there and pull and tear and bang and yank—it’s like working on a car. The body is very resistant, and it’s made of tough components. In order to make a change in it, you have to be aggressive. It was surprising, because I always thought of it as this very delicate procedure, like a dentist doing a filling.”

— Pippa Garner, in an interview with X-TRA

Garner viewed gender as another kind of product—mass-produced, stylized, and reinforced through visual cues. By modifying her appearance, she enacted a kind of conceptual art in motion. Her performances of femininity weren’t just personal; they were public disruptions of cultural coding. She used wigs, outfits, and behavior as tools of commentary.

Her work from this period often blurred boundaries between self and object. In her illustrated books like Utopia—or Bust! Products for the Perfect World, she inserted herself into imagined ad campaigns, further destabilizing the distinction between real and unreal. This use of the self as medium made Garner a forerunner of today’s digital identity artists.

Rather than transition privately, Garner embraced visibility. She defied the pathologizing narratives that often accompany transgender lives by reframing her story as one of joyful reinvention. In doing so, she became a beacon for queer artists seeking permission to design themselves on their own terms.

Art + Activism

Though not an activist in the traditional sense, Garner’s entire body of work can be understood as political. By transforming everyday objects and defying gender norms, she issued a quiet rebellion against systems of control. Her interventions were subtle but radical: What if a car didn’t need to make sense? What if a woman was self-designed?

Garner didn’t march or campaign, but she rewired the logic of consumerism to reveal its violence and absurdity. Her "inventions"—like genderless clothing or mechanized prosthetics—poked fun at the way society forces people into categories. She exposed the capitalist fantasy that happiness can be purchased, gender can be packaged, and identity is something to be sold.

“I guess the word "consumerism" guided a lot of things I did. I just liked the way that things got cycled through and then discarded, the idea that things got obsolete so quickly, and I felt sorry for them. It’s like I never outgrew my childhood notion of wanting to bring things to life, with my backwards cars and collaged t-shirts.”

— Pippa Garner, in an interview with Cultured

Her use of humor was a potent weapon. Laughter, for Garner, was a form of dissent—a way to disarm and destabilize. Her art revealed how absurd the “normal” truly is, turning the tables on a culture that demands conformity while claiming to celebrate uniqueness.

“Mass production is this furious way of stuffing the world full of things that people don’t know they need. Advertising needs to convince you that you do. I think that’s clumsy and it wastes a lot. It’s certainly not good for the environment, all the factories pouring out stuff. I noticed on the news today, it said China’s having trouble right now because there’s a coal shortage that’s caused all these factories to have to cut back, and they’re even threatening possibly having power outages in communities during the winter. It’s almost a panic situation, and it’s, “Oh, what are they making?” They’re making the things that aren’t necessary anyway. Mass production creates a superficial culture, because people are thinking in terms of something that catches their eye, that they don’t care about the next day. I think that automobiles epitomize all that. It’s an extremely complex thing. Cars take a huge, vast amount of energy to create, from virtually every conceivable resource. And what is it for? So that we can have urban sprawl. So that we can let our communities get completely sloppy. Urban sprawl has destroyed the centrality, the necessary focus of a community. In this little module, the car, you seal yourself up, lock the doors, and go out and swear at other people on the road because they’re cutting you off. All that stuff, little incidents like that, add up to a real decline in the culture, socially, in our ability to have enlightenment and vital communities.”

— Pippa Garner in an interview with HIGHSNOBIETY

In her later years, Garner was embraced by a new generation of queer and trans artists who saw her work as a blueprint for survival. She showed that subversion could be playful, personal, and deeply transformative—and that art need not scream to be revolutionary.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pride Palette to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.